|

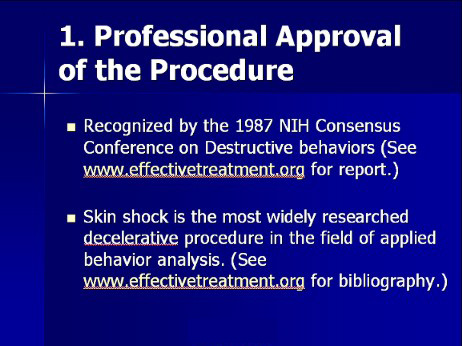

The use of skin-shock as a behavior modification punishment procedure is the most widely researched and scientifically supported punishment procedure in the psychological literature. This web site contains an extensive bibliography of research articles documenting the effectiveness of skin shock as a punishment procedure. Skin shock is not generally used in treatment programs today. This is due to an

unfortunate current cultural bias against aversive treatment procedures as well

as a general lack of information among the public concerning skin shock’s

remarkable effectiveness, its total lack of negative side effects, its safety,

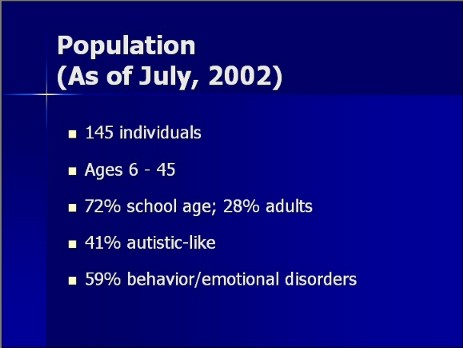

and the fact that students often choose it over alternative treatments. The Judge Rotenberg Center (JRC) first began using skin shock in 1989 in order to provide life-saving treatment to individuals who otherwise would have been unable to be successfully treated. Because this treatment was so effective, JRC has employed skin-shock with many of its students during the past 13 years with constantly increasing success. At this point JRC has accumulated the most extensive experience with the use of skin shock of any organization. The purpose of this paper is to make the most important aspects of this information available to others. The JRC Population JRC is a residential school/treatment center that currently (July, 2002) serves 145 individuals. Exhibit 1 summarizes their characteristics. Seventy-two percent are of school age, with a median age of 17 and a range from 6 to 21. Twenty-eight percent are adults with a median age of 31, and a range from 22 to 42. The students have a wide variety of diagnoses. Fifty-nine percent have behavior/psychiatric disorders. The remaining 41% are developmentally disabled and/or autistic-like. At any given time JRC's population includes up to four individuals who are part of a short-term respite program that JRC operates for the Massachusetts Department of Mental Retardation.

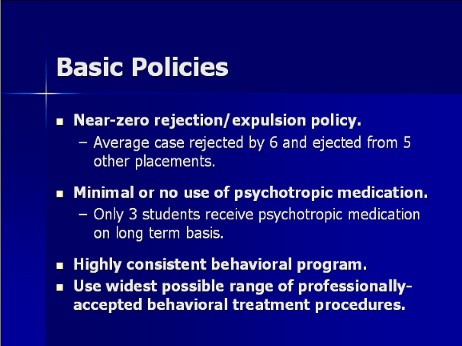

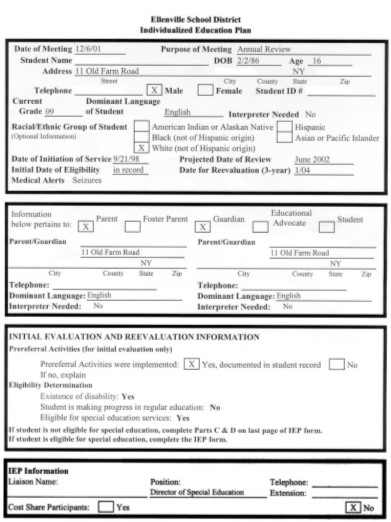

All of the individuals served by JRC live in JRC-operated residences and attend the JRC day school. JRC does not currently serve any day students but anticipates admitting day students in the fall of 2002. Basic JRC PoliciesJRC's key policies are these (Exhibit 2):

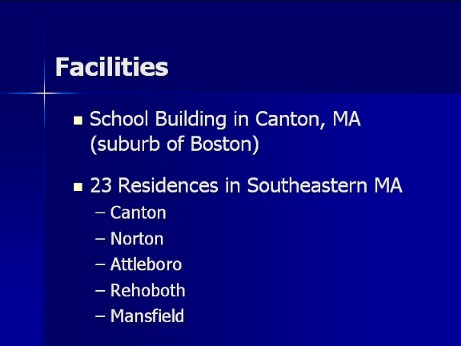

JRC's FacilitiesJRC's facilities (Exhibit 3) include two administration/school buildings (Exhibits 4 and 5) on an 8 acre campus in Canton, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston, and 23 residences in nearby communities. JRC's residences are located in Canton, Stoughton, Mansfield, Norton, Attleboro and Rehoboth, Massachusetts. All of JRC's residences are normal homes or apartments in suburban or semi-rural locations that blend in with the surrounding neighborhoods. Exhibits 6 through 20 show JRC's residences.

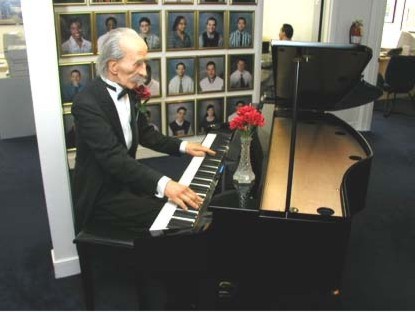

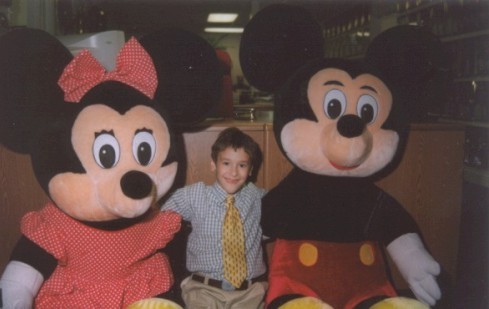

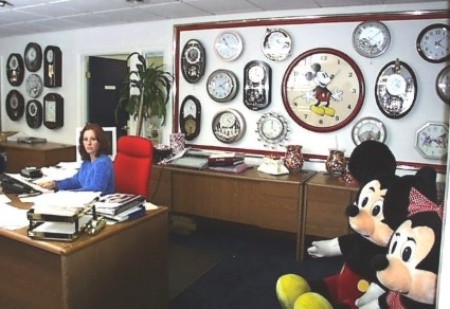

A Tour through the JRC school/administration building The first room one sees, upon entering JRC, is a very colorful reception area (Exhibit 21) with some bright and cheery Mickey Mouse prints. As we pass the reception desk (Exhibit 22) we see two life-like mannequin sculptures of policemen (Exhibit 23) who provide building security and a mannequin sculpture pianist (Exhibit 24) in formal dress tickling the ivories of a player piano. Turning the corner to enter the main hallway we are greeted by big Mickey and Minnie (Exhibit 25). Looking down the main hallway we see three of our secretaries busy at work (Exhibit 26). Behind them is a collection of 25 music-and-movement clocks (Exhibit 27). and some sculptures of candies (Exhibit 28). (The one on the left is real the one on the right is a sculpture.) On the right side of the corridor is a wall of framed portraits of current and former students (Exhibit 29). At the end of the hall is a mannequin sculpture of a seated Freudian psychologist with a pipe (Exhibit 30) here accompanied by two of our real clinicians. At the end of the hall is the office of our executive director (Exhibit 31) whose office features some modern acrylic sculptures and a large bowl of M&M's (Exhibit 32).

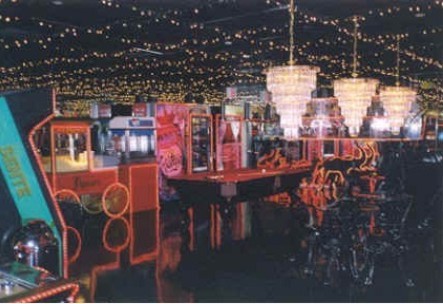

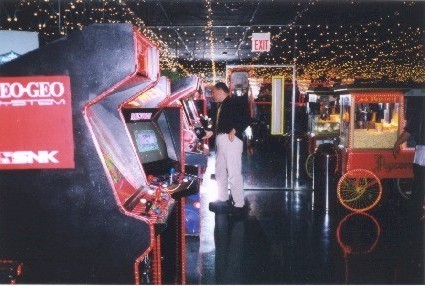

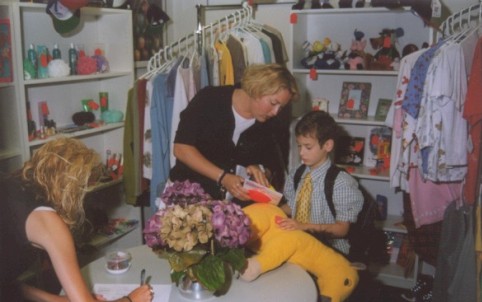

As we turn the corner we pass walls containing Mickey Mouse prints from many decades and artists (Exhibits 33 through 35) and offices that are also decorated with colorful prints (Exhibit 36). Next is a section with neon prints (Exhibit 37). These are just outside the Big Reward Store (Exhibits 38 and 39) which is a focus of the JRC reward system.

As we continue, we pass the exercise room (Exhibit 40), we pass by a few classrooms for some of our highest functioning students (Exhibits 41 and 42) and the Library (Exhibit 43). After turning another corner we pass the monitoring room (Exhibit 44) where staff monitor all areas of the building throughout the day and the nursing office (Exhibit 45) Then we come to the contract store (Exhibit 46) where students can choose items that they can earn by showing desired behaviors over specified periods of time.

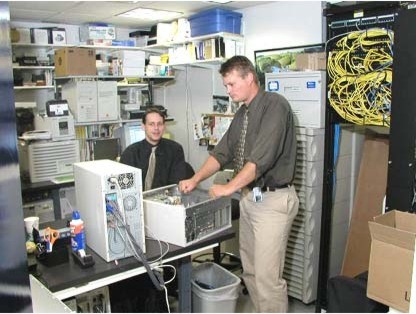

The Mickey Room (Exhibit 47) is where many new parents have their first meeting with members of JRC's admission department. Another mannequin sculpture (Exhibit 48) of a proctologist (here shown with our real nurse) stands in front of the entrance to the computer department (Exhibit 49) which oversees a network of 185 staff computers and one of 125 student computers. Our Andy Warhol foyer features beautiful Warhol prints (Exhibit 50), funky furniture (Exhibit 51), and a little mannequin sculpture of a little old lady gardener (Exhibit 52).

A classroom for some of our youngest students comes next (Exhibit 53). Then comes our Chagall Conference room (Exhibits 54 and 55) which features prints by the famous French painter of that name. Across from it is a collection of fun antique miniature cars beneath prints of Monaco racing posters (Exhibit 56).

The stairwell to the lower level (Exhibit 57) has a Coca Cola theme with nostalgic Coke ads, sparkling rope lights and two metal dog sculptures (Exhibit 58) at the bottom. The foyer of the lower level features modern aluminum furniture (Exhibit 59), a wall of artistic clocks (Exhibit 60), a waterfall (Exhibit 61) with fantastic animal sculptures (Exhibit 62) and a bubbling tree with a sculpture dog known as the Golden Reliever (Exhibit 63).

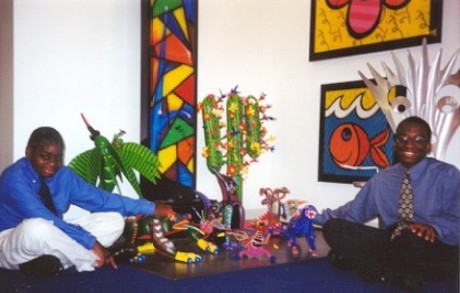

The lower level contains most of our classrooms. We start by passing walls of colorful prints by the contemporary Brazilian artist Britto (Exhibit 64), and then walls with prints by Lichtenstein (Exhibit 65). Off of this corridor are the classrooms for our newest students (Exhibits 66 and 67) and several classrooms for our autistic students (Exhibits 68 and 69). Then we pass through a corridor of Tarkay prints (Exhibit 70) leading to our multi-purpose room (Exhibit 71) that serves as our lunch room. It is decorated with Coca Cola ads from many decades and has a player piano (Exhibit 72) and CD jukebox (Exhibit 73). A mannequin sculpture chef (Exhibit 74) stands outside the lunch room and just down the corridor is a mannequin sculpture cleaning lady (Exhibit 75) here shown with our own real cleaning lady on the left. We walk down a corridor lined with Bukovnik prints (Exhibit 76) on one side and with impressionist prints by Dufy (Exhibit 77) on the other and enter our work activities training room (Exhibit 78) and our work activities center (Exhibit 79). After turning the corner, we come to two corridors which feature Warhol prints (Exhibits 80 and 81) and which contain several more classrooms (Exhibits 82 and 83).

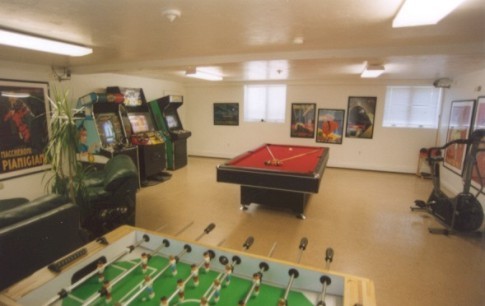

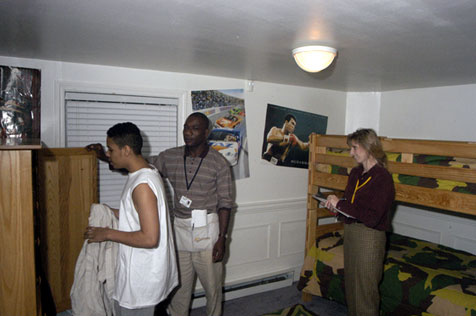

It should be evident from these photographs that we have gone to extraordinary lengths to create a warm, happy, colorful décor in our buildings. A walk through our building is a uniquely interesting experience in itself--something like a cross between a beautiful museum, miniature theme park, interesting store and lovely home. We deliberately made our school so attractive an environment that our students would actually like to come to school! A Tour through one of the JRC residences We pay equal attention to the choice of, and decoration of our residences. Here are some views from one of our residences called Old Maple: a living room (Exhibits 84 and 85), kitchen (Exhibit 86) den (Exhibit 87), dining room (Exhibit 88), bathroom (Exhibit 89), playroom (Exhibit 90) and, from another one of our residences, an outdoor swimming pool (Exhibit 91).

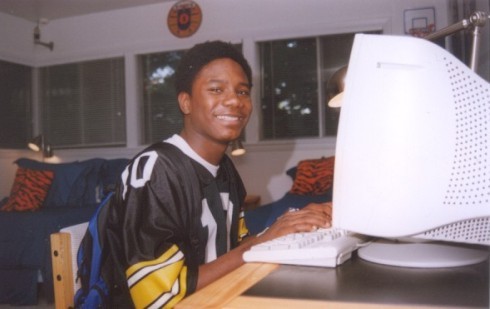

Exhibit 92 shows a bedroom in the Old Maple house. The students decorate their own bedrooms. We provide cable TV, stereo, a CD/DVD player and Sony Playstations in each bedroom (Exhibit 93). The students must earn the time to enjoy these through their behavioral contracts and points. In the bedrooms of many of our higher-functioning students a computer is provided that the student can use when doing his or her homework (Exhibit 94). In houses for lower functioning students there is at least one computer for the house.

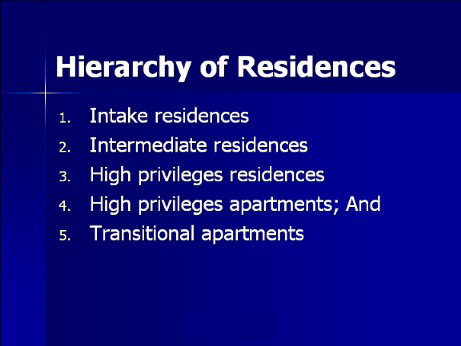

All of our homes are carefully and tastefully designed with the aid of a highly skilled decorator-consultant. We furnish each common area with beautiful, non-institutional furnishings and colorful prints. A staff of special monitors visits all of our residences on a frequent basis to make sure that they remain in the same clean, well-furnished condition that they were in when originally furnished. Photographs of each interior space of each of our residences may be seen on our web site, www.judgerc.org. When students first arrive at JRC, they live in one of our larger and highly staffed residences that specialize in handling new admissions. Each of these "Intake Residences" serves 8-12 students. While students are living in one of these Intake Residences, they come to the school building 7 days a week and their school day extends to 8:00 pm each evening. As the students' behaviors improve, however, they advance to smaller homes and apartments that have fewer staff members and students (some have as few as four students), more privileges and a more normal schedule for attendance at the school. There are five categories of residences which are shown in Exhibit 95. Just as a student can advance from one residence to another by showing desired behaviors, undesired behaviors may cause the student to move back to a lower step on the residences ladder until his or her behavior improves.

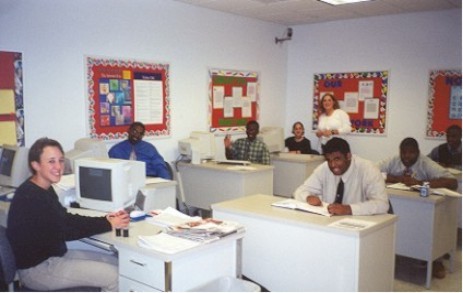

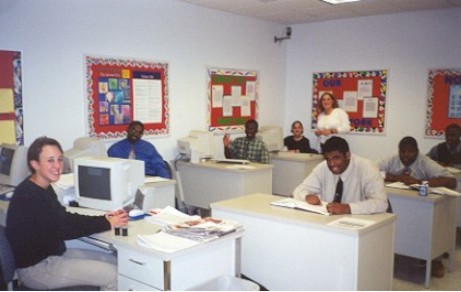

More detailed information concerning this residence ladder is available in Exhibit 96. The JRC Educational ProgramEducational Program for Higher Functioning Students JRC is certified as a special needs school by the Massachusetts Department of Education. JRC makes as much use of behavioral technologies in the classroom as is possible. For example, we make extensive use of computers that present individualized self-instructional programs. To accomplish this, JRC's own staff has developed a variety of self-teaching software in key areas such as phonics, reading, math, spelling, and vocabulary. We use precision teaching to measure and advance student progress. In precision teaching, rates correct and incorrect, rather than percent correct, are used to evaluate student progress. The teacher or the student plots daily data for each academic skill on standard behavior charts. These enable the teacher, as well as the teacher's supervisors, to monitor the student's progress daily and to act quickly to remedy any lack of progress. Exhibit 97 shows a classroom for some of our higher functioning students. Notice that there is a dress code in which both students and staff wear shirts and ties when in school. Each student has a pedestal desk. Almost all of our higher functioning students are provided with their own personal computer.

Exhibit 98 is another classroom for higher functioning students in which each student is working at his or her own computer. If the total number of computers at each JRC residence is added to the total number in the classrooms, the ratio of computers to students is 1:1. The student computers are networked and database software allows both the teachers and the educational administrators to keep track of each student's progress on their own desktop computers. This network also allows students to view their own behavior charts to see their progress and to send email messages to staff members.

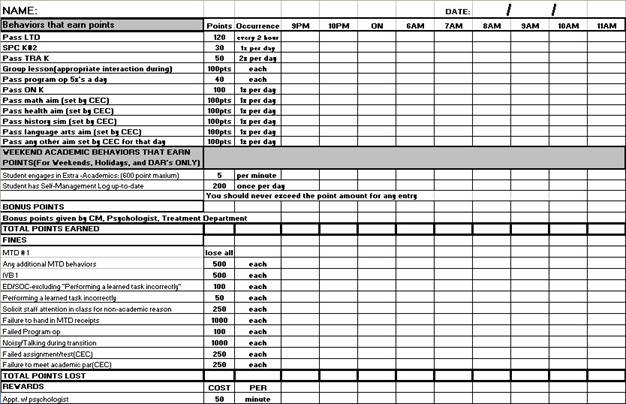

A "token economy" point system is used to motivate the students to learn. A separate point sheet (Exhibit 99) is used to keep track of the points each student has earned during the day. Students must earn points or tokens in order to purchase various rewards that the school makes available. A certain percentage of these points must be earned through the student's academic performance and a certain percentage must be earned by meeting treatment objectives. These percentages are individually determined for each student and are changed as needed.

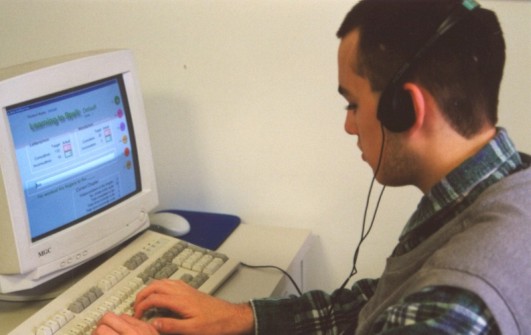

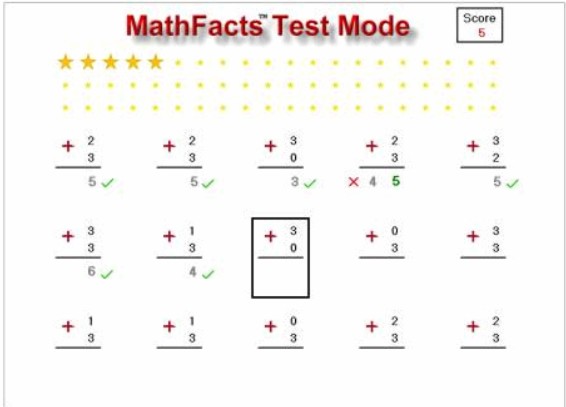

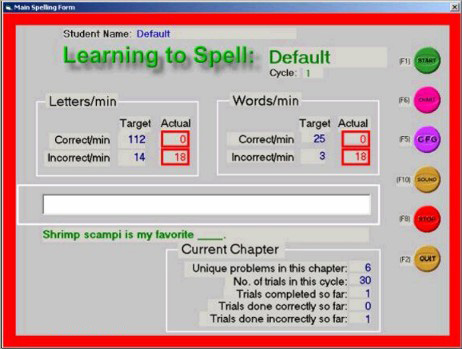

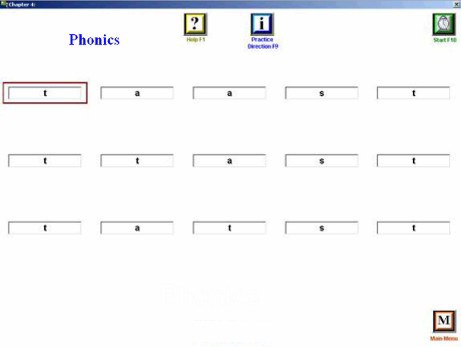

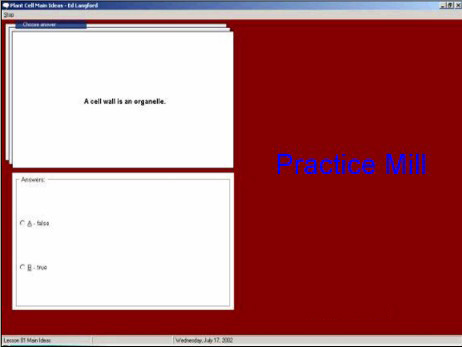

Because commercially available educational material is generally not designed in accordance with principles of behavioral psychology, JRC has designed much of its own educational software. Each higher functioning student has his/her own computer and uses this software both at the school and at his/her residence (Exhibit 100). Exhibits 101-104 show screen shots of custom computer programs that JRC's software development staff have designed for use with JRC's higher functioning students in key areas such as phonics, reading, writing, spelling, vocabulary and math. These sample screen shots are taken from our programs to teach math facts (Exhibit 101), Spelling (Exhibit 102), Phonics (Exhibit 103) and science (Exhibit 104).

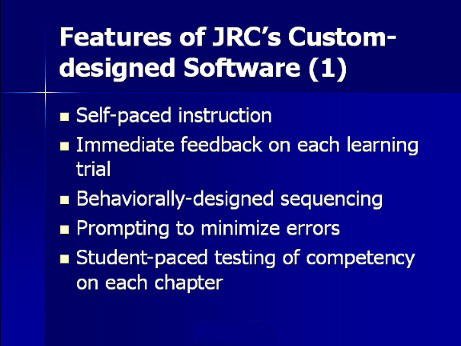

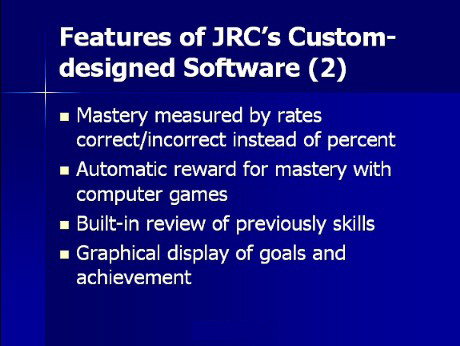

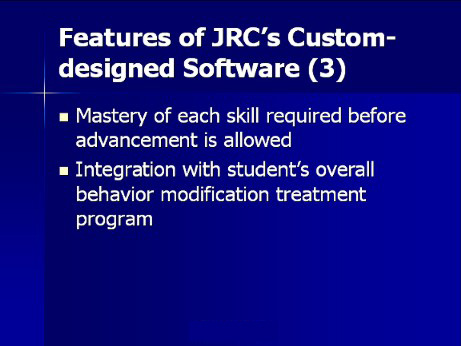

The important features of this software are listed shown in Exhibits 105, 106, and 107 and are as follows:

An important by-product of JRC's heavy reliance on computers and software is that all of our students become computer literate. Students use the computers to record their own self-management behavior data and to display it in graphical form. They also use them the practice writing business letters and to send email messages. Each student is taught to type using typing software and most achieve a level of skill in typing that can be a valuable office skill to help secure a job. Exhibit 108 shows another form in which some of JRC's educational material is presented-flash cards. The math facts curriculum and the phonics curriculum are made available both through our custom-designed computer software as well on flash cards. Flash cards make it easy for the student to set aside the problems he/she has learned and concentrate on those that need further study. The student times himself with a timer, and when his rate correct and rate incorrect have reached the target levels, the student asks the teacher for a timing test. If the student passes the timing test, he or she is advanced to the next chapter or skill.

In addition to the self-paced learning using computers and flash cards, JRC also provides group instruction so that students will be able to handle more traditional means of instruction when they return to public school (Exhibit 109).

Exhibit 110 illustrates another aspect of JRC's program-teaching students the responsibility that is involved in having a child. This is called the "Baby Think it Over" program. Each of our higher functioning students is required to spend a week taking care of a simulated, computerized "baby" that cries at unexpected times throughout the day and night, must be "fed" regularly (by inserting a key into slot), etc. Once a student spends a week or two taking care of the computerized baby, he or she is likely to think more responsibly about creating a baby and is less likely to think of it as a lark.

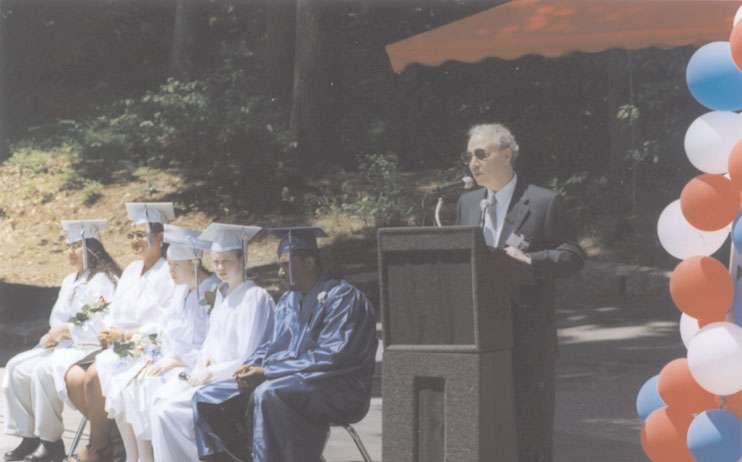

JRC prepares students for the high school competency examinations required by their home state such as Massachusetts' MCAS exams and the New York State Regents Exams. Some students have earned their local high school diploma through their academic work at JRC. Other students may earn an IEP diploma, a Certificate of Completion, or a Certificate of Attendance from their home school district that is awarded at JRC Culmination/Graduation ceremonies (Exhibit 111). For more details about JRC's educational program please see Exhibit 112.

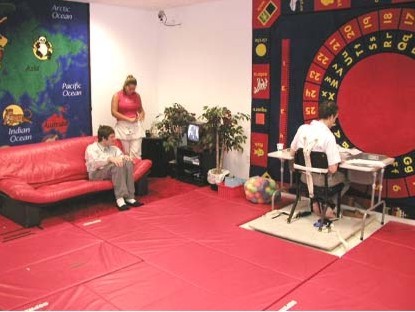

Educational Program for Lower-Functioning Students Exhibits 113, 114 and 115 show a few of the classrooms for our lower functioning students. Notice that each of these classrooms has a reward area within the classroom, access to which must be earned by appropriate behaviors. In it the students may sit on a couch or armchair and watch TV, listen to music, play a game or just relax with peers. Exhibits 116, 117, 118, 119, and 120 show a closer view of these classroom reward stores.

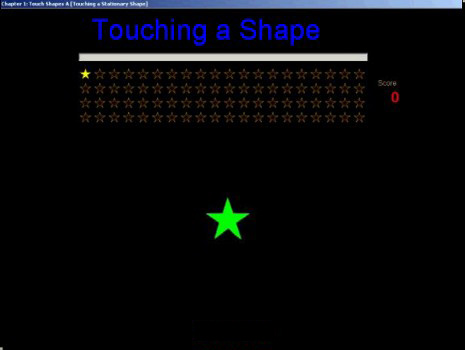

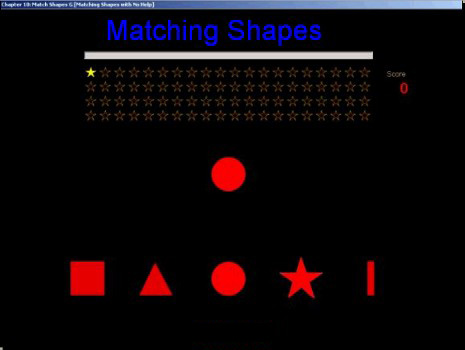

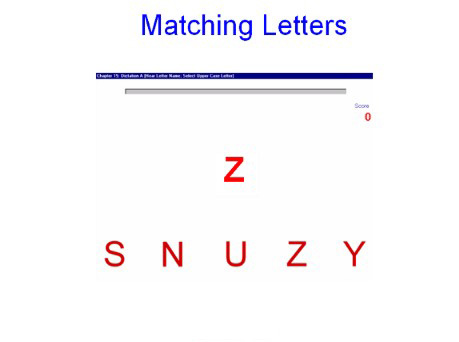

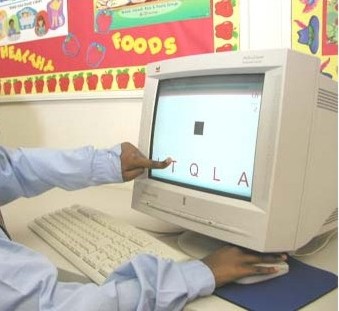

JRC's lower functioning students also use computers and JRC-designed custom software for much of their instruction (Exhibit 121). Responses are usually entered by means of a touchscreen. The software is basically designed for self-instruction, but requires occasional participation by a teacher or aide to administer rewards. The software teaches students how to point, how to match shapes, letters and numerals, and how to point to the appropriate picture of an item when its name is given by the computer. Most important, the software teaches the student how to use his or her pointing skills to choose a reward and how to ask for something by saying the name of the item.

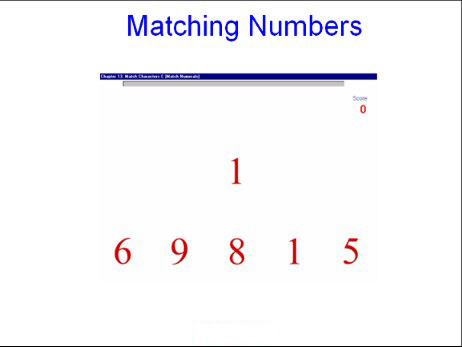

Exhibits 122-128 are some screen shots taken from this software. Exhibit 122 is from a program to teach the student to touch a form wherever it appears on the screen. Exhibit 123 is from one that teaches matching forms. This leads to matching letters (Exhibit 124), matching numbers (Exhibit 125) and then selecting a letter or number after hearing its name (Exhibit 126). Exhibit 127 is from a program to teach receptive vocabulary in which the student hears the name of an item and then must point to the correct item. Other programs teach the student how to use a computer mouse (Exhibit 128).

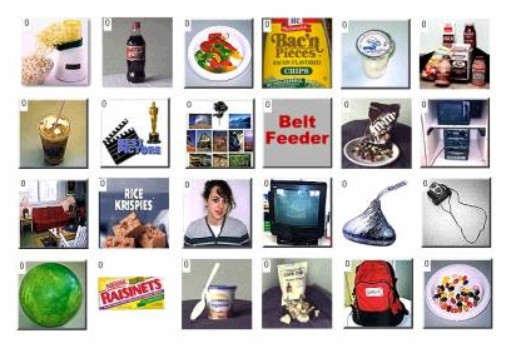

There are two types of reward systems used with this software. For some students we use an automatic reward dispenser (Exhibit 129) that dispenses a small food reward to the student automatically after he or she has completed a certain number of problems. For most students, when the student has completed a certain number of problems on the computer a special screen comes up on the student's computer (Exhibit 130). This screen flashes once per second and also emits a periodic beeping noise. Its function is to signal the teacher to come over to the student and to reward him/her for having completed a certain number of problems. When the teacher comes over to the student, the teacher presses a certain key combination that brings up a pictorial reward screen on the student's computer (Exhibit 131). The student now points to the picture of what he/she wants for a reward (Exhibit 132) and vocalizes the name of the item. (The teacher provides a prompt for this vocalization if needed.) The computer screen then displays a larger picture of the reward that the student has chosen (Exhibit 133) and the teacher now delivers the reward that the student has asked for (Exhibit 134).

Pre-vocational and vocational training The JRC behavior modification treatment program automatically teaches a number of important job skills. Most important is, of course, how to follow directions of one's supervisor, how to be courteous and polite and how to dress appropriately for the job. All JRC students also learn certain specific skills that are useful today's work environment, including typing and computer use. For students who are unable to work in competitive environments, JRC operates a Work Activities Center (Exhibit 135) where students work on various assembly jobs that JRC contracts to do for local businesses.

JRC purchases training slots for several of its at the Blue Hills Regional Vocational School, a public vocational training high school located near JRC. Our students have taken courses in culinary arts (Exhibit 136), small engine repair, and graphic communications and in the future will be taking courses in woodworking and carpentry. This school also helps its students obtain entry-level jobs in the vocational areas in which they have been trained.

Whenever possible, JRC provides part-time paid jobs within JRC (Exhibit 137) which students at all levels can do. Students who develop the necessary behaviors and skills are also able to graduate to do competitive jobs, without support from JRC staff, at local businesses (Exhibit 138).

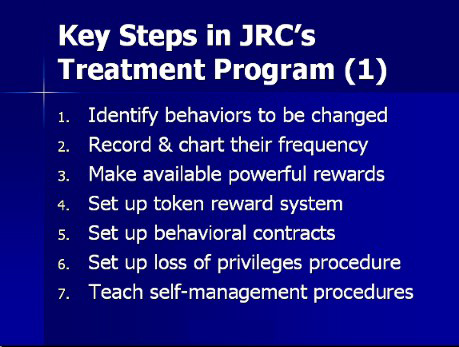

The JRC Treatment Program Exhibits 139 and 140 present the key steps in JRC's behavior modification treatment program. Each is explained in greater detail below.

1. Identify the behaviors to be changed (Exhibit 141). At JRC we analyze the student's problems in terms of sets of behaviors that need to be increased or decreased in frequency. By the term "behaviors" we include externally-observed behaviors such as overt actions as well as internal behaviors that are more difficult to observe, such as thoughts feelings, emotions and urges. We have found it convenient to categorize problematic behaviors as belonging to one of seven broad categories, which are these:

If a particular student needs more than these seven standard categories, additional categories are created. And if a clinician wishes to divide one of these categories into smaller sub-categories, he/she may do this. Most of the target behaviors we initially seek to change are external, observable behaviors. However, as the external behaviors improve, internal behaviors, such as the student's thoughts, feelings, urges and emotions, tend to show an automatic improvement. For example, as the student begins to pass behavioral contracts, succeed in his/her academic work, etc., he/she feels better and his/her self-concept, self-esteem and confidence improves.

2. Record and chart the frequencies of the behaviors (Exhibit 142).

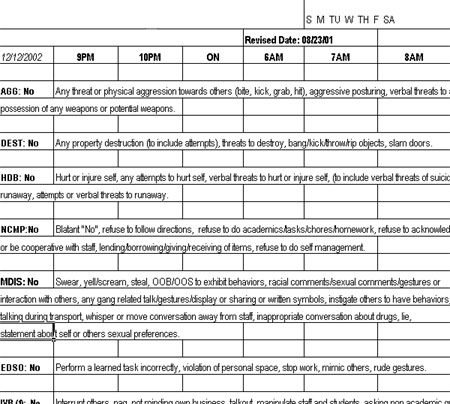

At JRC we record the daily frequencies of each of these major behavior categories. This recording is done around the clock, 24 hours each day, seven days a week. To accomplish this, a "Daily Recording Sheet" (see Exhibit 143) is prepared for each student. It has a separate row for each of the major categories of problem behaviors. The name, or abbreviation, of each category is listed at the left end of its row in capital letters, and to the right is a listing of the specific behaviors that will be recorded as part of this category. Each of the columns is for one hour of the day. If the student exhibits a certain targeted behavior, the staff member makes a mark in the cell that is at the intersection of the row for the behavior, and the column for the time when it occurred. The number of marks at the end of the day shows the number of times that the behavior occurred on that day. That data is then entered in a database by a member of the charting staff at JRC and software converts the data in the database to daily, weekly, monthly and yearly charts.

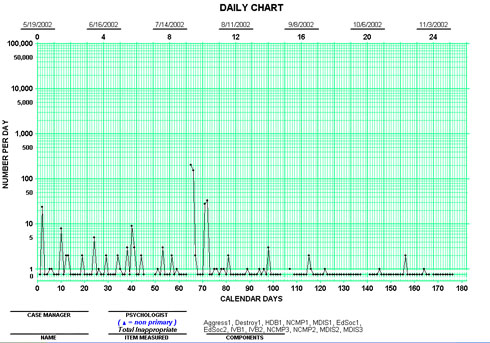

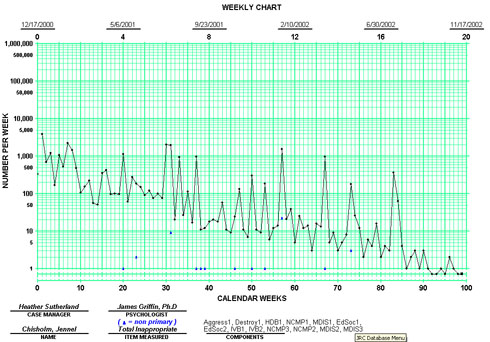

Exhibit 144 shows a typical daily behavior chart that we use. The vertical scale is logarithmic. This enables us to use one standard chart that can accommodate a very wide range of behavior frequencies-anywhere from 1/day to 100,000/day. When an important change is made in the treatment procedures-e.g., the introduction of the skin-shock procedure-a vertical "intervention" line is drawn to indicate when this change was made and to help the reader of the chart interpret whether the intervention appears to be associated with any subsequent changes in the behavior's frequency.

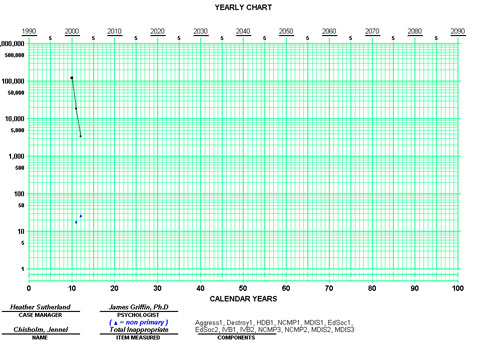

The software automatically plots the same behavior data on weekly (Exhibit 145), monthly (Exhibit 146) or yearly (Exhibit 147) charts so that trends over longer periods of time can be detected.

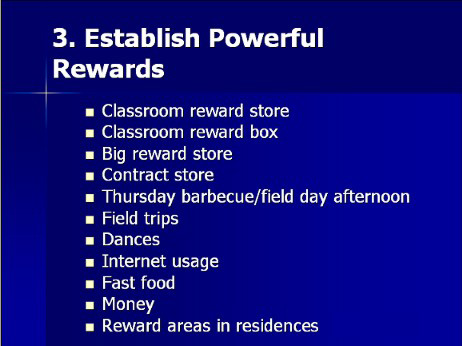

Our system of charting makes use of the principles and procedures known as Precision Teaching or Standard Celeration Charting, which was developed by Dr. Ogden Lindsley and his students. The same type of charting system is used to measure positive behaviors that the students are taught in their educational program. In some cases, the software we use has a built-in charting system. 3. Establish a powerful set of rewards that the student will want to earn (Exhibit 148).

At the heart of any successful behavior modification system is a set of rewards that the student will want to earn. Some of the most prominent at JRC are these (the list is only partial):

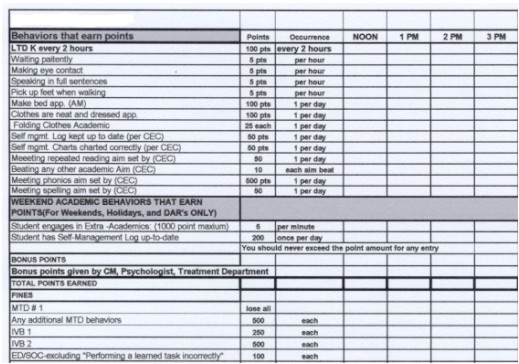

4. Set up point or token reward systems (Exhibit 159).

These are systems in which points can be earned by the display of target behaviors and the points can be spent to purchase rewards. For some lower functioning students, pennies may be used instead of points. Each student who earns and spends points has a "point sheet" (see Exhibit 160) that specifies what behaviors earn points, how much various rewards cost in points and what the maximum number of points are that the student is allowed to earn in one day.

5. Arranging a system of behavioral contracts (Exhibit 161). Contracts are arrangements in which if the student goes for a specified period of time without displaying certain specified problem behaviors, he or she earns a specified reward at the end of the contract period. If, however, the student exhibits the specified problem behavior(s), the contract is "broken," a new contract is set up and the student tries again. There are many types of contracts that are used at JRC. Normally several will be used at the same time for a given student.

Sometimes the student must pass a certain contract in order to gain access to a place where the student's points or pennies can be spent. For example, the student might have a contract which, if it is passed successfully, allows him/her to go to the Big Reward Store. Once there, however, the student must have earned some points in order to purchase the items that are available in the Reward Store. See Exhibit 162 for a more complete description of various contracts that JRC uses with a typical student. 6. Establish a "Loss-of-Privileges" (LOP) procedure (Exhibit 163). If the student displays certain major inappropriate behaviors, all opportunities to earn contract rewards or to spend points are suspended. At JRC we call this a "Loss of Privileges" period. The duration of the LOP can vary from minutes to several weeks. Sometimes an LOP status may be combined with shifting the student's residence or classroom to place him in a more highly staffed and less desirable residence or classroom.

7. Teach self-management procedure (Exhibit 164).

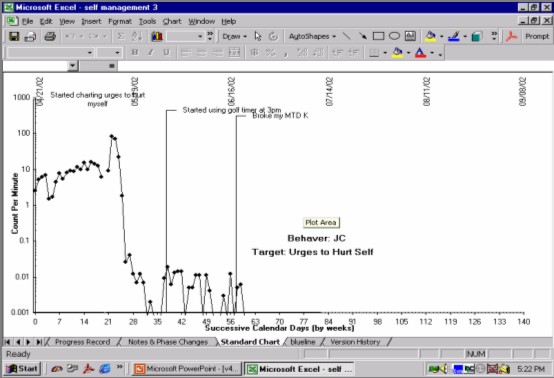

Each of the higher functioning students are taught to select at least one "outer" problem behavior (such as being aggressive) and one "inner" behavior (such as having urges to be aggressive), to count and chart those behaviors, and to select and arrange their own rewards or penalties to change the frequency of the behaviors. Exhibit 165 shows the chart of a student who is counting his urges to hurt himself. The students meet each week (Exhibit 166) with other students and with a supervising clinician or other staff member to share the data, display their behavior data and discuss their behavior management techniques.

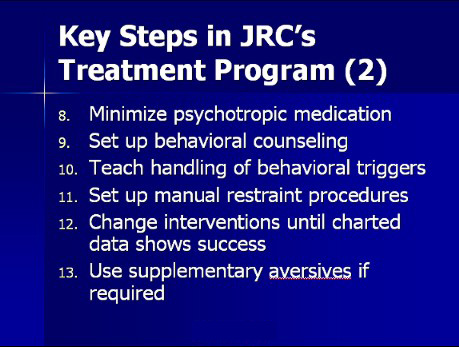

8. Minimize or eliminate the use of psychotropic medication (Exhibit 167) If a student is on medication when he or she enrolls at JRC, the medication may be removed under the guidance of a psychiatrist. Psychotropic medication is employed only if the charted behavior data support the need to use it as an adjunct to JRC's behavioral treatment program. More information about JRC's policies in this area may be found at www.judgerc.org

9. Insure that all counseling is behaviorally oriented. (Exhibit 168)

It is important that all aspects of the treatment program, including any counseling (Exhibit 169) that is provided to the student, be fully coordinated with the rest of the JRC program and that the counseling be conducted and offered in a behavioral manner. See www.judgerc.org for further details on JRC's policies on behavioral counseling.

10. (Exhibit 170) Teach the student to cope successfully with events that normally trigger problem behaviors ("Programmed Opportunities"). It is important to important to identify those stimuli and events that normally trigger the occurrence of the student's problem behaviors. These should be presented to the student on planned occasions; the student should be taught how to cope with these successfully; and he/she should be rewarded when he does so.

11. Set up Safety Procedures to Handle Aggressive Behaviors Safely. (Exhibit 171) If a student displays violent behaviors that are a danger to him/herself or others, JRC employs emergency manual restraint in a safe and carefully supervised manner.

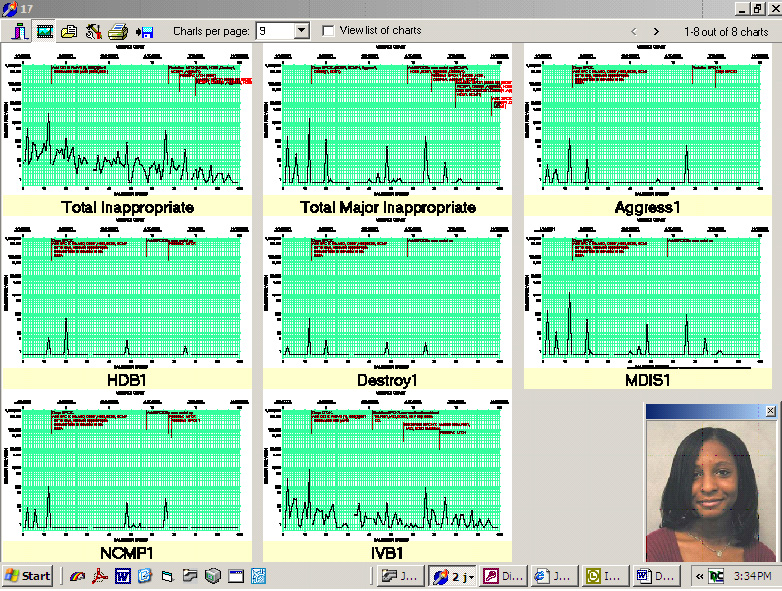

12. Changing the components of the treatment system until the charts show the desired changes in behaviors (Exhibit 172). At JRC a behaviorally-trained doctoral psychologist or clinician, assisted by the student's case manager, and with consultation from others such as the nurse, psychiatrist, and classroom teacher, oversees the progress of each student. The clinician is responsible for reviewing the charts on a regular basis, meeting with the student from time to time, entering progress notes and writing progress reports, and making changes in all interventions until the treatment program is working with sufficient effectiveness. At JRC the philosophy is that the student is never "wrong." If the student is not behaving the way we want him or her to behave what is wrong is simply the current set of interventions-they need to be changed until they work more effectively. The clinician who supervises the treatment team is held responsible for making the needed changes. Each week one of the clinicians presents the charts of his or her students at a "data sharing" session (Exhibit 173) attended by all of the other clinicians, case managers, other administrators and the executive director. JRC's charting software makes it possible to display all of the important charts of each student on one screen at the same time in "thumbnail" views, as shown in Exhibit 174. This type of display enables all behaviors being treated to be reviewed quickly and to enables relationships among them to be seen easily.. The group makes suggestions for improving the treatment and becomes immediately aware of any case where a student is not progressing satisfactorily. In effect, through these sessions the group holds the clinician responsible for producing progress in all of the students under his or her care.

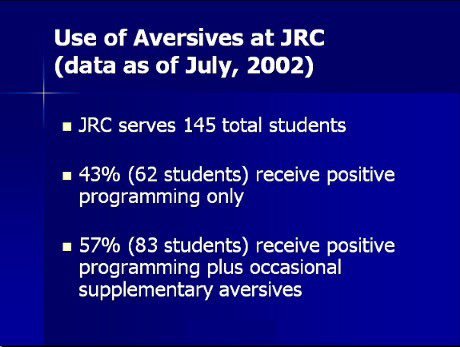

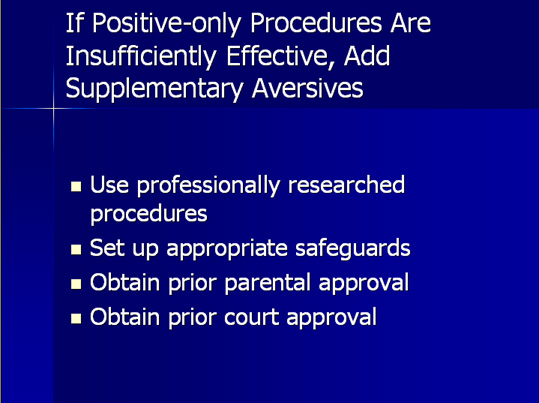

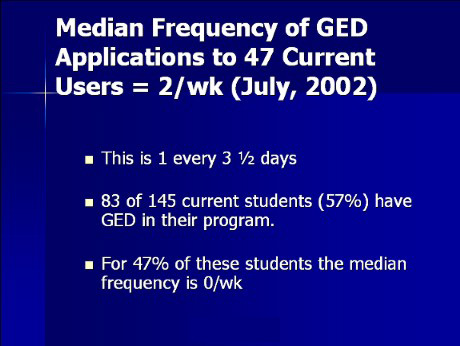

Use of Supplementary Aversives at JRC Many of the students placed at JRC have been exposed to positive-only, non-aversive procedures in their past placements, but these were not affective. It is likely, however, that none of the students have previously been exposed to as rich, consistent and as highly structured a positive behavioral program as JRC offers. For many of JRC's students, therefore, JRC's positive only, treatment systems prove to be sufficiently effective, by themselves, to produce satisfactory treatment progress. For example, of JRC's current students, this has proven to be the case for approximately 43% of those students (see Exhibit 175). In such cases, JRC is able to accomplish effective treatment with its positive programming systems alone, and does not need to consider the possibility of adding supplementary aversive procedures to the treatment package.

For the remaining 57%, however, positive treatment procedures alone may not be sufficiently effective. For these students who prove to be resistant to positive-only treatment, JRC is able to supplement its positive-only treatment systems with aversives, providing JRC has prior parental consent and court approval. The aversives employed at JRC are safe, effective and professionally approved and are used only with prior parental and court authorization (Exhibit 176). If JRC seeks and obtains court authorization to employ supplementary aversives, this authorization also permits, in the typical case, the use of both mechanical and manual restraints to be applied as supplementary aversives. JRC's use of aversives is discussed in the remainder of this paper. A videotape illustrating the aversive procedures JRC uses, together with case history material from students who have used them, is available from JRC upon request. The supplementary aversive employed at JRC in most cases is a brief, harmless remote-controlled skin-shock described in more detail below. For many individuals, this skin-shock treatment is required only during the first few months of treatment, and is no longer necessary or is necessary to a far lesser and diminishing degree, after that period.

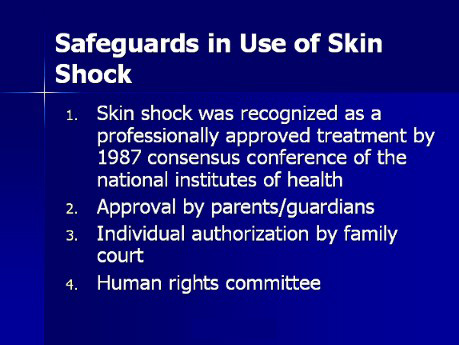

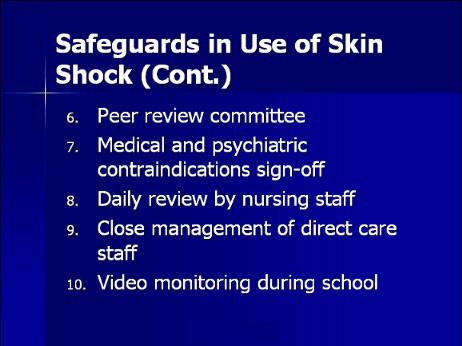

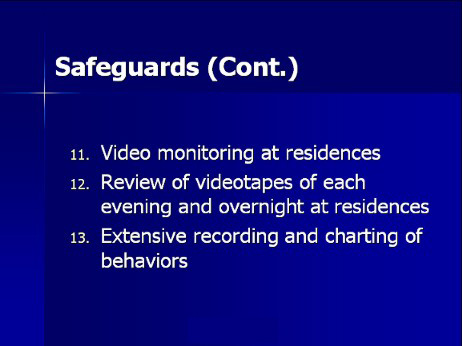

Safeguards JRC's use of aversives is carried out carefully, openly and with a maximum number of safeguards. The safeguards are listed in Exhibits 177 through 179.

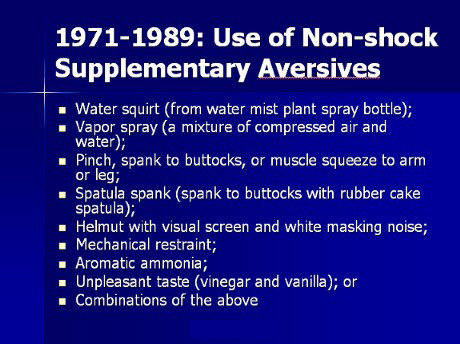

1971-1989: Use of Non-shock Supplementary Aversives From 1971, when JRC was founded, through 1989, the supplementary aversives JRC employed were ones that did not involve the use of skin shock. The procedures that JRC employed as aversives during that period are listed in Exhibit 198: 1. Water squirt (from water mist plant spray bottle); 2. Vapor spray (a mixture of compressed air and water); 3. Pinch, spank to buttocks, or muscle squeeze to arm or leg; 4. Spatula spank (spank to buttocks with rubber cake spatula); 5. Helmet with visual screen and white masking noise; 6. Mechanical restraint; 7. Aromatic ammonia; 8. Unpleasant taste (vinegar and vanilla); or 9. Combinations of the above.

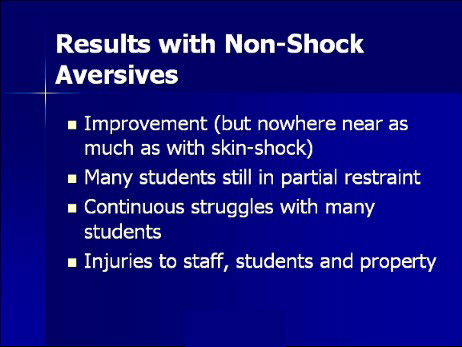

Exhibit 199 summarizes the overall effect of these procedures. They enabled JRC to provide dramatically effective treatment to individuals with extremely difficult behavior problems. However, for some students, they were insufficiently effective. As a result, some students still required the use of partial mechanical restraint systems. In addition, struggles were sometimes required to put students into restraint or to administer the aversives. Sometimes these struggles-which some students appeared to enjoy-may have functioned as an unintended reward. And there were more cases of injuries to staff, students and property than was desirable.

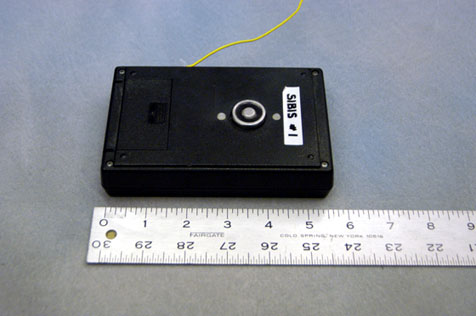

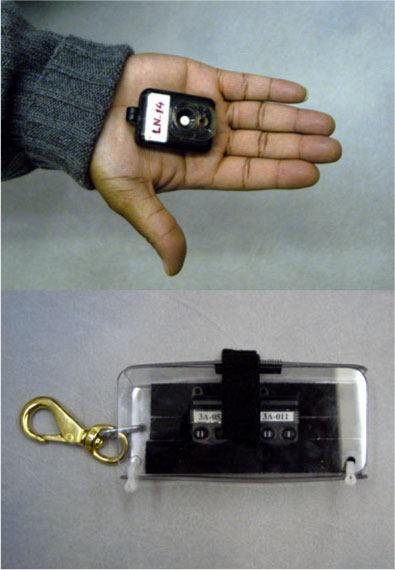

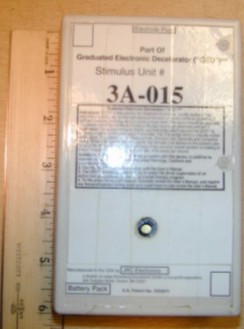

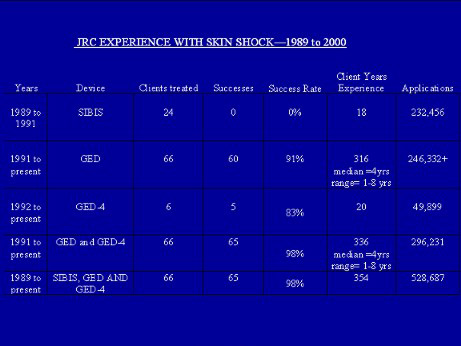

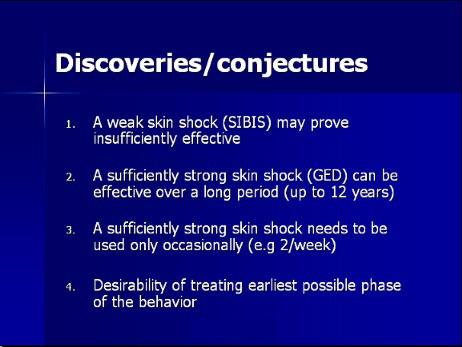

1989-90: Use of the SIBIS Device JRC first began using skin shock in 1989 in order to provide life-saving treatment to individuals who otherwise would have been unable to be successfully treated. Because this treatment was so effective, JRC has employed skin-shock with many of its students during the past 13 years with constantly increasing success. At this point JRC has accumulated the most extensive experience with the use of skin-shock as an aversive of any organization. In 1989 JRC decided to try the use of a commercially available skin shock device called SIBIS (Self Injurious Behavior Inhibiting System). This device had been invented by a parent and had been re-designed by engineers at the Johns Hopkins University. Exhibit 200 shows the unit that generates the shock. The button and ring shown in the middle of the device is the electrode that delivers the shock. Exhibit 201 shows an associated remote control device.

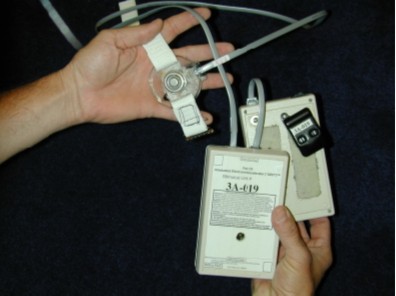

In JRC's use of the SIBIS shock device, the SIBIS transmitter was attached to the arm or leg with an elastic band as shown in Exhibit 202. When so attached, button-and-ring electrode that protrudes the SIBIS chassis makes contact with the skin. The operator activates the device with a hand-held remote control device similar to a remote control garage door opener. When the remote control is activated, it sends a coded electromagnetic signal to a radio receiver that is a component of the SIBIS unit. When this receiver receives the signal, another component of the SIBIS device generates an immediate shock to the skin of 2.02 mA (rms).

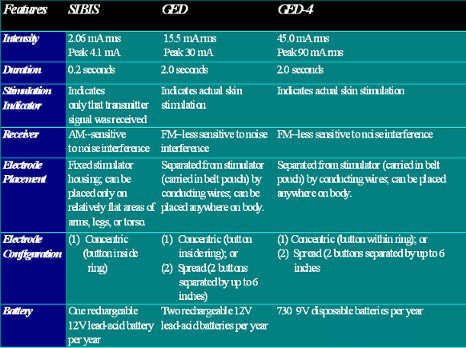

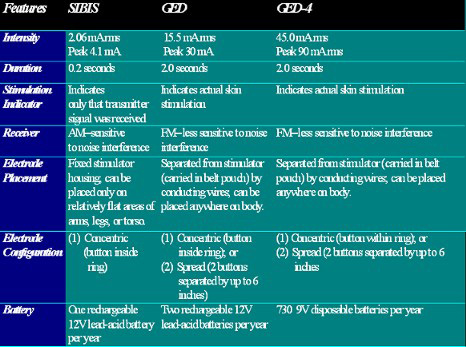

Exhibit 203 (column 1) gives some of SIBIS' important characteristics as compared with two other devices that JRC subsequently designed, the GED and the GED-4. The SIBIS device produced a 0.2sec shock to the surface of the skin that had an average intensity of 2.02 mA (rms).

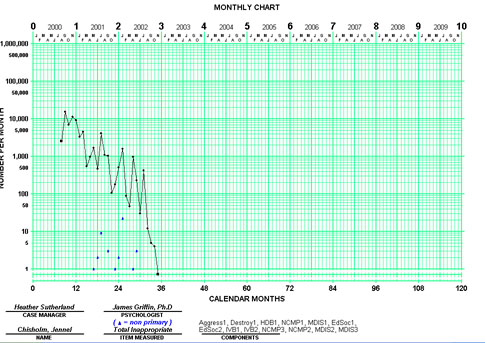

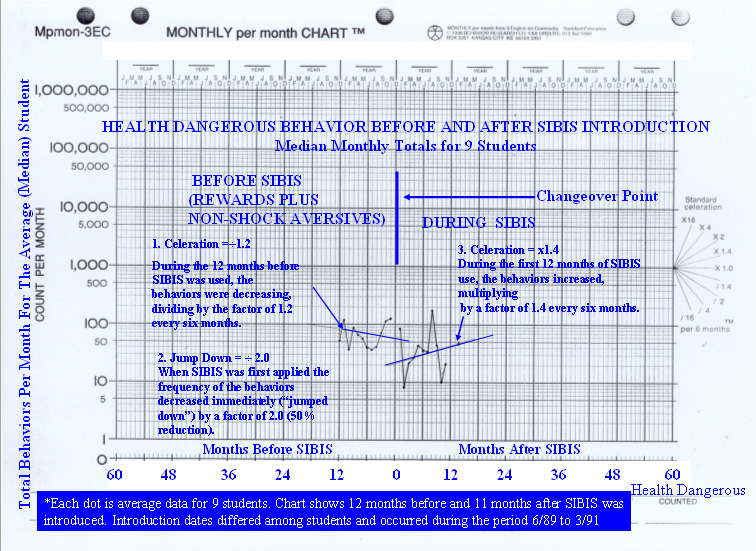

Exhibit 204 is a chart that summarizes JRC's experience with the use of SIBIS. This chart is a Standard Behavior Chart (developed by Dr. Ogden Lindsley) that shows behavior frequency on the vertical axis and calendar months on the horizontal axis. The vertical scale for behavior frequency is logarithmic to accommodate a wide range of behavior rates. Exhibit 204 incorporates data from 9 different students and shows the average monthly frequency of their health dangerous behaviors during the 12 months before the use of SIBIS and during the 11 months after SIBIS was introduced. During the 12 months before SIBIS was introduced, each student was receiving non-shock supplementary aversives such as a pinch, spank, etc. When SIBIS was first introduced in the treatment of these students, it was substituted for whatever non-shock aversives were being used at that point.

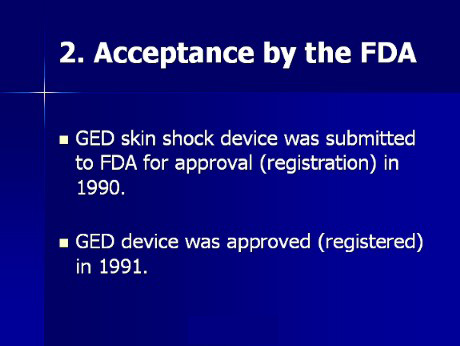

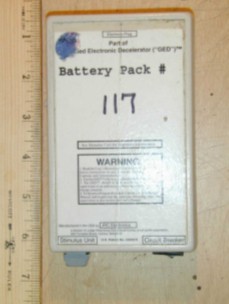

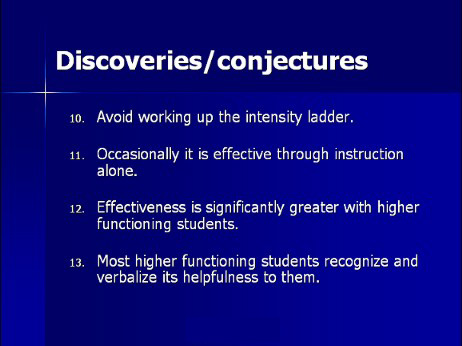

The actual date on which each of these 9 students started on the SIBIS device was different for each student; however, to make a comparison possible we have plotted the data as though each of the students started using SIBIS at the same "changeover" point. This changeover point is shown by a heavy vertical line on the chart. The data points to the left of the changeover point show the average monthly behavior frequency on the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc. months before the changeover point. The data points to its right show the average monthly frequency on the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc. months after the changeover point. This chart shows that SIBIS was effective at first, but lost much of its effectiveness after a few months of use. Overall, the problem behaviors were decreasing gradually before the use of SIBIS, although the last four months of this period showed an upward trend. When SIBIS was introduced there was an immediate drop in frequency during the first two months, but thereafter the behaviors began to increase in frequency. One obvious problem with the SIBIS device was that the stimulus was relatively weak. A clear indication of this was that JRC staff members would routinely test the device on themselves each day to make sure it was working. JRC asked the manufacturer to increase the strength of SIBIS, and to make several other desired changes, but was unable to secure the manufacturer's cooperation. 1990-date: Development of the GED and GED-4 Devices At that point, JRC decided to develop its own skin-shock device, which was called the Graduated Electronic Decelerator, or GED. A stronger version of the GED, called the GED-4, is also available. The GED consists of several components.

Exhibit 213 is a table that indicates the principal differences between the GED and the SIBIS. The SIBIS characteristics we describe were true of the SIBIS units JRC purchased in 1989-90. We have not examined the most currently available version of SIBIS to see whether any changes have been made in the unit since that time. The most important of the differences between GED and SIBIS are these:

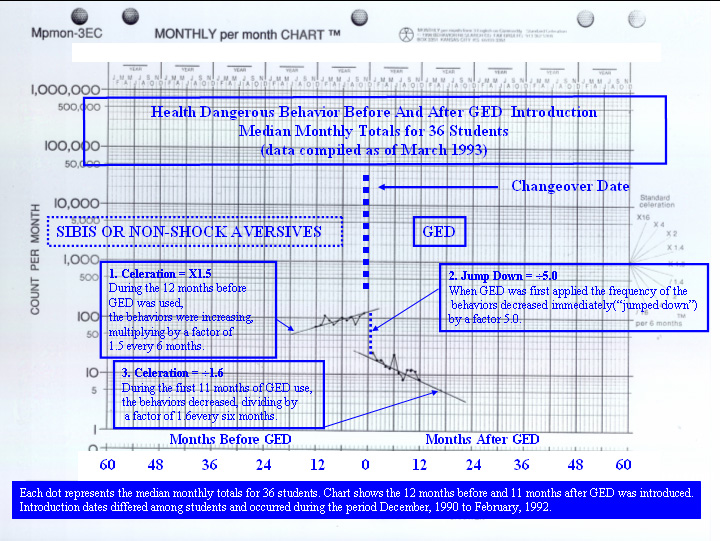

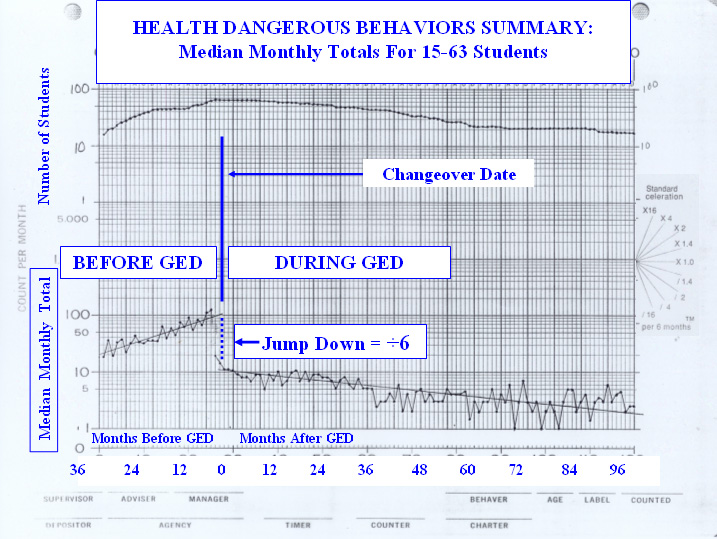

Comparison of GED with SIBIS Exhibit 218 is a chart comparing the effectiveness of the GED with SIBIS, in decelerating the health dangerous behaviors of 36 students at JRC during the years 1990-1992. Health dangerous behaviors include self-injurious behaviors of various kinds. In the case of each of these 36 students, SIBIS was used for at least 12 months, after which the GED was substituted for SIBIS.

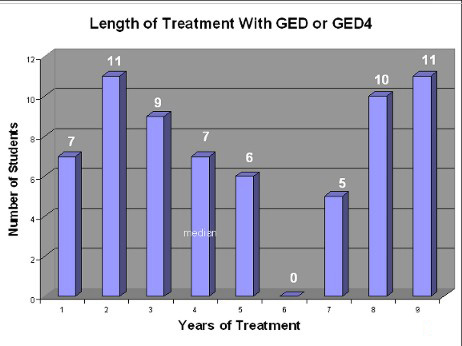

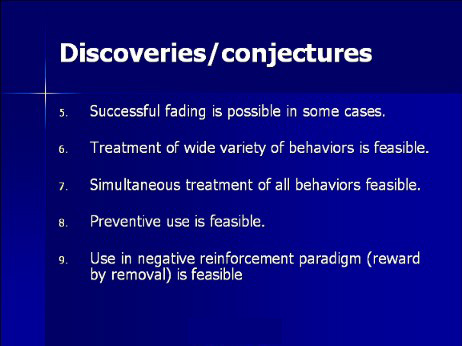

As in the chart shown earlier, although the actual date on which the change from SIBIS to GED was different in each of the 36 cases, the data for all 36 students have been synchronized and plotted as though the changeover took place on the same "artificial" changeover date for all 36 students. The vertical dotted line in the middle of the chart represents this artificial changeover date. The 12 data points to the left of this line represent the 12 months immediately before this artificial changeover date-12 months during which SIBIS was being used to decelerate the behaviors. The 11 data points to the right of this line represent the 11 months immediately after this artificial changeover date-months during which GED was being used. Each of the 23 data points on this chart is a median of 36 individual monthly totals of Health Dangerous behaviors. The chart shows two important effects on these median monthly totals. First, the introduction of GED caused an immediate drop in the median monthly totals. The median dropped precipitously from a level of 120/month in the last month of SIBIS to a level of approximately 22/month on the first month of GED. This represents an immediate improvement (decrease in the median monthly totals) by a factor of almost 6. In addition, the chart shows a second effect. Although the behavior was getting steadily worse (accelerating) during the last 12 months immediately before the introduction of SIBIS, it was getting steadily better (decelerating) during the first 11 months of GED use. More precisely stated, although the monthly total was multiplying by a factor of 1.5 every 6 months during the last 12 months of SIBIS the GED caused it to change from this acceleration to a deceleration. After GED was introduced the data show the median monthly totals dividing by a factor of 1.6 every 6 months during the first 11 months of GED. In summary the GED proved to be very effective in both immediately dropping the frequency of the problem behaviors and in producing a continuing further improvement after it was introduced. These results were so encouraging, that in 1992 we discontinued the use of SIBIS and substituted the GED in its place for all students with whom we were at that time using SIBIS. Exhibit 219 shows the length of GED treatment that students have received at JRC as of July, 2000. As of that date, we had used the GED or GED-4 to treat 66 students. The median length of time the GED or GED-4 had been used with those students was 4 years with a range from 1 to 9 years.

Exhibit 220 is a table that summarizes our overall experience with the use of GED skin shock from 1990 through July 2000. During that period we treated 66 individuals with the GED. Of these 66, 60 students, or 91%, were successfully treated. By "successfully treated" we mean that their problematic behaviors reached and remained at either zero or low, non-problematic levels ever since the initial introduction of the GED.

Development of the GED-4 In 6 (8%) of the cases, however, the GED lost its effectiveness over time. To cope with this loss of effectiveness, in 1992 we designed a stronger version of the GED, called the GED-4. This device produces the same stimulus as the GED except that the current is stronger-45.0 mA rms compared with the 15.25 mA rms for the GED. In five out of six of these cases, the change from the GED to the GED-4 was sufficiently effective to bring the behavior back under control again. In one case the introduction of the GED-4 was only partially effective. In this case we have to use continual partial mechanical restraint to keep the student safe. This is restraint that allows the individual to walk and work, but prevents sudden aggressive actions against other students or staff. Nonetheless, although this student is in partial restraint at all times, his quality of life is significantly better than it was prior to the use of aversives and also better than it would be if aversives had to be discontinued. He has been able to come off the use of psychotropic medication, and he is able to spend his days doing productive work. He is able to use and enjoy the internet, and has been able to avoid placement in a state hospital or state facility for the developmentally disabled. At the present time we are developing a third version of the GED which we hope will be more effective than the GED-4 with this student. This version seeks to improve effectiveness by using a chain of multiple applications in which the pulse duration, interpulse intervals and chain duration are variable and software controlled. Frequency of Use Currently JRC has 145 students. Of these 83 have court-authorized treatment plans that permit the use of the GED in their treatment. Among these 83 students the actual use of the GED or GED-4 is surprisingly rare. Exhibit 221 shows the data on usage as of July 2002. The average (median) number of applications given to the 83 current users of the GED or GED-4 has been 3.5 applications per week. This represents only 1 application every 2 days.

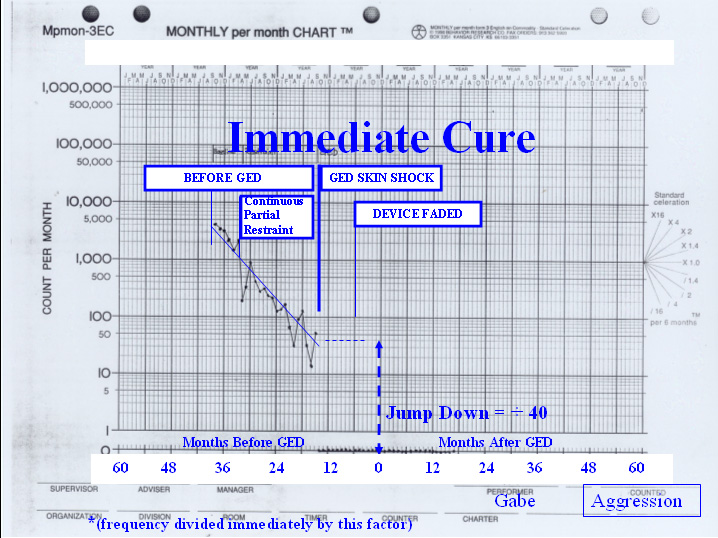

The reason for this is primarily that the GED treatment is so effective that the behaviors being treated occur very rarely and, as a result, receive aversives very rarely. In addition, JRC arranges various rewards to encourage students to advance to the point where they do not need to wear, or receive applications of, the GED device. When the student's behavior improves sufficiently, the student is no longer required to wear the GED device and the device is kept on the shelf. In a few cases, we have gone back to court and asked to have it removed from the student's treatment plan because it was no longer needed. An anecdote will illustrate the low frequency of the user of the GED. A few years ago we had a psychologist visiting and working with us for a three-week period. He was frustrated at the end of his visit that he had never witnessed an actual application of the GED. Individual Charts Illustrating Techniques and Results Immediate Cure (G.R.) Exhibit 222 shows a monthly chart for G.R.'s Aggression. Each dot shows the total number of aggressive behaviors per month.

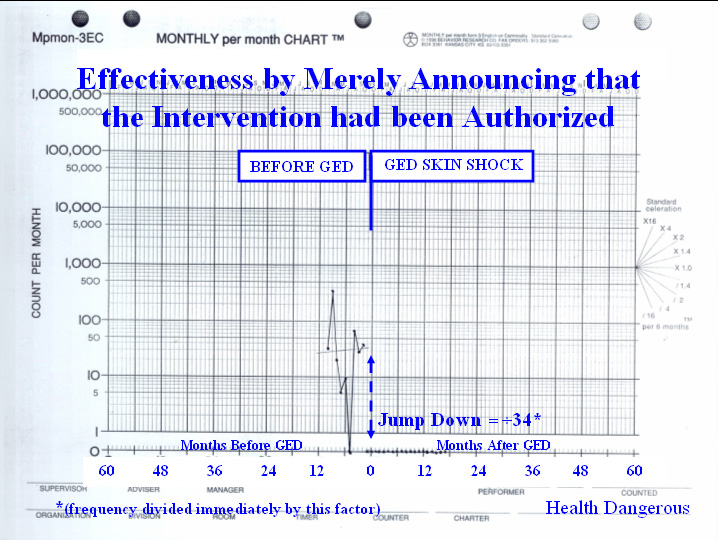

During the first month he showed 4,000 aggressive behaviors (about 133 per day). In G.R.'s case we deliberately worked for over two years to try to treat his aggression and other problem behaviors with nonaversive procedures alone and without recourse to the use of the GED. During those two years his aggression steadily declined, but much of the decline was due to the use of continuous partial mechanical restraints. After two years of this he was still showing approximately 50 aggressive incidents per month, had completely destroyed his bedroom many times and caused many injuries to staff members and other students. After 25 months we obtained permission from a probate court to use the GED. The behavior immediately decreased to a zero rate and has stayed there ever since. Notice that G.R. received no applications of the GED for this behavior (aggression). He did receive a few applications for some of the other inappropriate behaviors he was showing. So GED treatment of one or two of those other behaviors also appears to have affected his aggressive behavior without the GED having to be applied to this behavior at all. Mere Announcement of Court Approval to Use GED as an Effective Intervention (J.N.) With some of our higher functioning students, merely advising them of the fact that we had now obtained court approval for the use of the GED in their programs has functioned as an effective treatment procedure-without our ever having to actually apply the GED to their behaviors. One example is shown in Exhibit 223, which is a chart for student J.N.'s health dangerous behaviors. These behaviors were so severe that at one point she hit her head through a thick plate glass window at the front of our building as she walked through the foyer. The chart shows that as soon as the GED was made part of J.N.'s program she showed no dangerous behaviors at all after that point. No applications of the GED ever had to be made for this behavior after we told J.N. that the procedure had been approved for use and had her start wearing the device. We have had one other case in which the same thing happened.

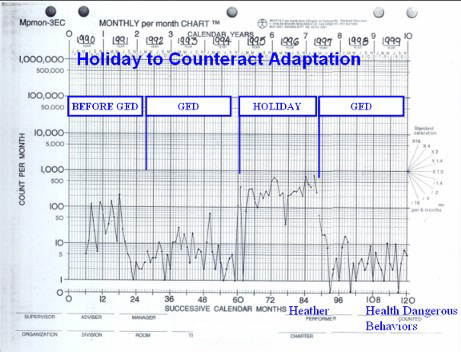

Adaptation counteracted by the use of a holiday from treatment (H.S.) One problem with the use of skin shock is that some students show adaptation to the stimulus. We saw this happen in the case of all the students with whom we tried SIBIS. It has also happened in a few cases with whom we used the GED. One thing one can do when this happens is to stop using the GED for a period of time in the hope that a sufficient "holiday" will stop the adaptation and enable the stimulation to recover its effectiveness when the holiday is ended and the stimulation is reintroduced. Exhibit 224 shows one case in which this strategy was tried successfully. The chart is for H.S.'s health dangerous behaviors. During the period prior to the introduction of the GED, H.S. was being treated with a spatula spank. While that treatment was used, H.S. showed between 10 and 100 health dangerous acts per month. When the GED was introduced in April of 1992, it was fairly successful and brought the behavior to a lower level. In December of 1994, however, the behavior suddenly increased to the same general level which it had shown prior to the introduction of the GED. At that point we tried a GED holiday that lasted for two years. During the holiday, the behavior was not consequated with any aversive and rose to even higher levels than it had shown in the "Before GED" period. In February of 1997 we ended the holiday and reintroduced the GED. The behavior returned to the levels it had originally showed when the GED was first introduced suggesting that the holiday procedure was successful.

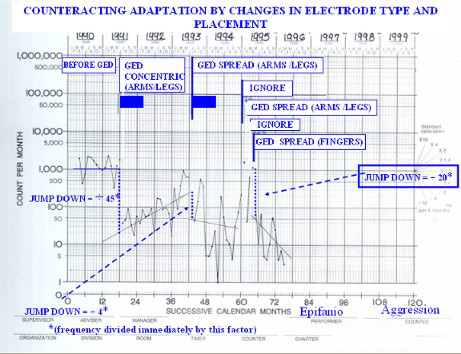

Adaptation counteracted by changes in electrode type and placement. Exhibit 225 illustrates changing the type of electrode (from concentric to distanced) and changing the type and location of the electrode, to cope with adaptation and improve the effectiveness of the GED. The chart is a monthly chart for E.T.'s aggression. Each data point representing his total aggressive acts in a single month. The chart shows that when the GED with the concentric electrode was first introduced in June of 1991, it had an immediate effect of dividing the monthly frequency by a factor of 45. However, over the course of the next 24 months, the frequency gradually returned to its originally high level. This phenomenon may be due to adaptation-the gradual loss of aversiveness, and hence of effectiveness, as a result of the use of the procedure over a period of time.

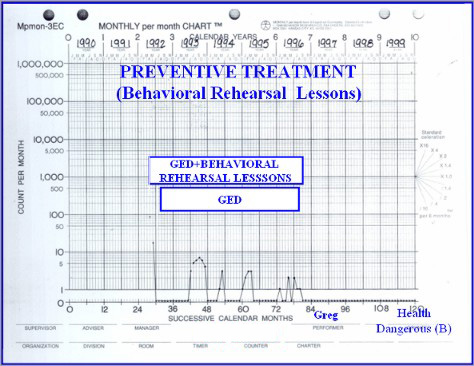

To counteract this adaptation, in June, 1993 we changed the electrode from a concentric type to a "distanced" type. This change caused the frequency to decrease immediately by a factor of 4 and also caused the behavior to decelerate over the next 15 months. However, in the last three months of 1994, the distanced electrode suddenly lost its effectiveness, and the behavior returned to a high level. After trying a few holidays in early 1995, during which the behavior was ignored rather than "consequated" (i.e., followed by the consequence) with the GED, we changed the body site at which the GED was applied. All previous applications with this student had been to the arms or legs. In April 1995 we applied the distanced electrode to the fingers instead of the arms and legs. This caused an immediate improvement (the frequency dropped by a factor of 20 and a subsequent steep deceleration occurred). This chart shows a case in which JRC needed to modify the treatment procedures constantly in order to maintain treatment effectiveness over a period of 6 years. Preventive treatment: behavior rehearsal lessons Exhibit 226 shows the use of the GED in preventive treatment. G.M. is student who had life-threatening self-injurious behaviors, including gouging his body with knives. G.M had already lost much of the sight in one eye through self-abuse when he began JRC. In his most recent placement, he had suffered a life-threatening pulmonary embolism due to the continuous periods of mechanical restraint he was subjected to in order to prevent further self-abuse. His most recent placement had referred him to the Mass General Hospital for a cingulotomy (surgical cutting of pathways of the brain) in order to try to stop his self-abusive behaviors. The neurosurgeon advised trying behavioral treatment first, and that is how he was referred to JRC. In G.M.'s case, we decided that even one instance of further self-abuse was too many. To prevent or minimize occurrences of the behavior, we gave G.M. a course of preventive treatment over a period of approximately 10 months. We called this treatment "behavioral rehearsal lessons." In each lesson, we required G.M. to engage in the beginning phase of one of the self-abusive actions in which he had previously engaged. For example, we required him to pick up a plastic knife and bring it toward his skin to try to cut himself. We forced him to do this even if he resisted. As soon as he engaged in this beginning form of the behavior, we administered the GED. At first we gave G.M. four such lessons a day, separated by three or four hours. After a few months, we made contracts with him that enabled him to reduce the number down to three per day if he avoided any problem behaviors. This number was then reduced to two per day, then to one per day and, after ten months, we dropped the lessons entirely. Exhibit 226 shows that during the entire ten months of these lessons, G.M. did not show the targeted behavior even one time. After the lessons stopped, he did show a few instances of attempts to exercise the behavior or the beginning phase of the behavior, and these were treated with the GED. He did not, however, ever show a full blown self-abusive action. G.M. now has a paid job doing maintenance and cleaning work at JRC.

Treating the Initial Phase of the Behavior; Use of Negative Reinforcement It is our experience that it is important to consequate a problem behavior at the very earliest stage at which it is observed to occur or to be about to occur. This means that the consequence should be administered as soon one sees any of the following:

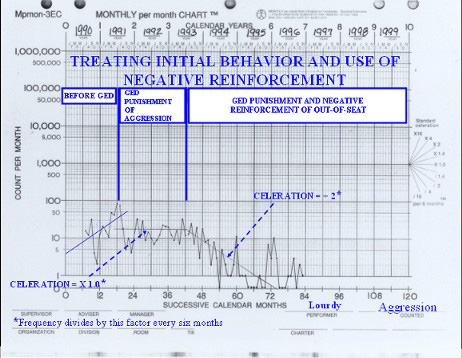

Exhibit 227 illustrates a case where the treatment of aggression did not become effective until we changed from consequating the full occurrence of the aggressive behavior to consequating the beginning phase of a chain of behaviors that typically ended in aggression. The chart shows the treatment of L.L.'s aggression over the course of nine years. The chart shows monthly totals of L.L.'s aggressive behavior during the years 1990 through 1996. As Exhibit 227 shows, during the 12 months prior to the introduction of the GED , L.L.'s aggressive behaviors were showing an alarming increase in frequency and by June 1991 had reached a level of 100 acts of aggression per month. The GED treatment was started that June, and caused an immediate drop to a level of approximately 20 per month. However, after that drop, the frequency showed no improvement after that, remaining at about 20 occurrences per month throughout the entire next two years. In June of 1993 we changed the behavior being treated. Most of the aggressive behaviors started with L.L.'s bolting out of his seat in the classroom and attacking another student or staff member. Prior to June of 1993 we had arranged the GED consequence as soon as he attacked the student or staff member. In June of 1993, we devised a scheme that would punish the very first member of the chain of behaviors that led to the aggression- which was bolting from his seat. We devised a chair that had a switch in it that would close as soon as he bolted from his seat. When the switch closed it activated the GED immediately. In addition, the GED continued to activate every 2 seconds until L.L. sat back down in his seat. This procedure involved the immediate punishment of getting out of his seat and the negative reinforcement of getting back into his seat (if the GED started to be applied, he could stop it by going back to his seat). We also taught L.L. that if he had a legitimate need to get out of his seat, for reasons other than to be aggressive, he would be able to do so by raising his hand to ask to get up. When he did so, the therapist turned off the seat-board switch and allowed L.L. to get up and go where he needed to go without receiving any GED applications. Exhibit 227 shows that as soon as we started the punishment and negative reinforcement of out-of-seat behaviors (in June, 1993), (instead of waiting for the full-blown aggression to occur), aggression began to decrease. As the chart shows, the behavior decelerated over the course of the next three and half years to minimal or zero levels each month.

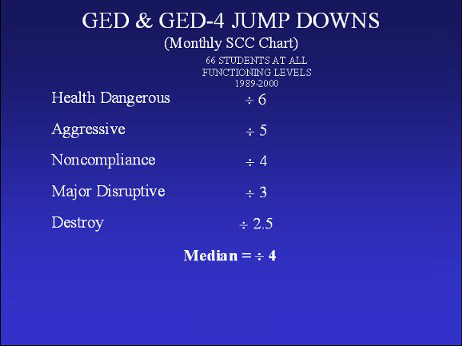

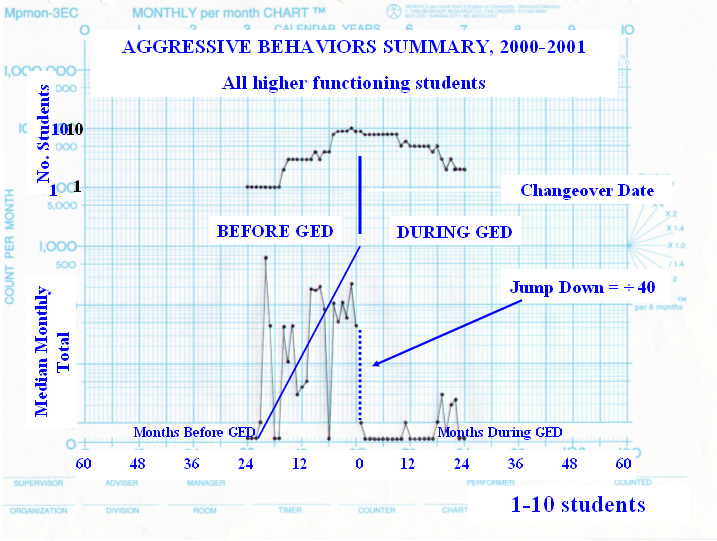

Summary Charts, 1989-2000 Examining the immediate drops in frequency, using data from 63 students, 1989-2000 Punishment often has two effects: (1) an immediate decrease ("jump-down") in the frequency of the behavior that takes place as soon as the GED or GED-4 is introduced; and (2) a change in the trend or celeration. We will first examine the effects on the immediate jump-downs in frequency. Exhibit 228 is an overall summary of the effect of the GED or GED-4 on the health dangerous behaviors of 63 students during the years 1989-2000. As in the previous summary charts presented above, this chart does not show actual calendar dates. Instead, it synchronizes the 63 individual charts around the "changeover" date on which a particular intervention was introduced. In this case the changeover date was the date on which the GED or GED-4 was first employed as an intervention. For these 63 students, the intervention that was used prior to the changeover date was either SIBIS or non-shock aversives. The labeled heavy black vertical line shows the "changeover date" around which the data were synchronized.

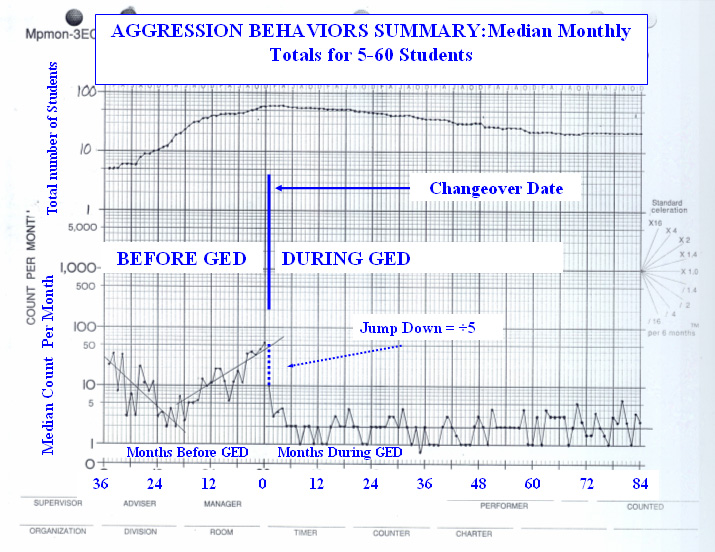

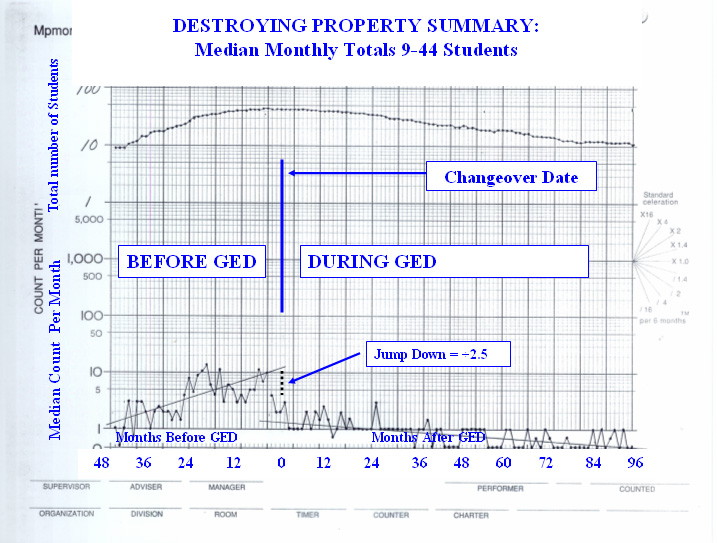

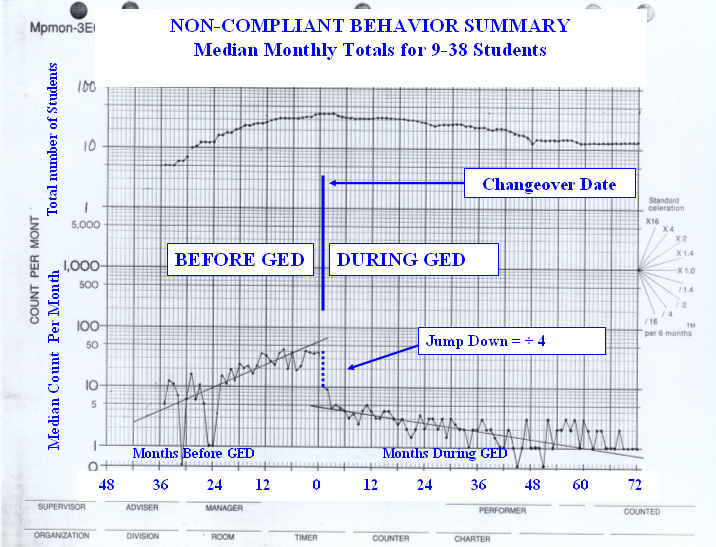

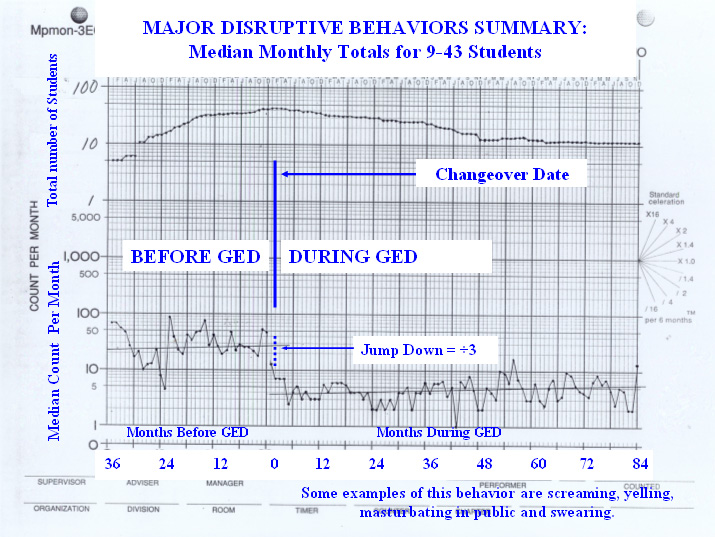

As in the summary charts presented previously, the data points to the right of this changeover date represent (reading from the changeover date to the right) the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc. months immediately after the changeover. The data points to the left of this line represent (reading from the changeover date to the left) the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc. months immediately before the changeover date. The number of students whose data are represented in each data point varies. For example, the first point on the chart (at the far left side of the chart) represents the 25th month prior to the changeover date. There were only 15 students, out of the 63 students, for whom we have data for the 25th month prior to the use of the GED. (This is due to the fact that some students were placed on the GED sooner than 25 months after their admission.) Therefore, that first data point is the median of only 15 monthly totals. By contrast, if we look at the 1st month immediately before the changeover date, that data point is a median for all 63 students. The same is true for the first data point immediately after the changeover date. The curve at the top of the chart shows the number of students who are represented in each of the data points that are plotted in the data series at the bottom of the chart. As you can see, the number of students starts at 15, rises to 63 at the changeover date and then gradually declines to 8 students in the last data point on the far right side of the chart. Because the number of students represented in each data point changes, the most valuable part of this chart are the 10 data points that are based on all 63 students. These are the data points that start on the 2nd month immediately before the changeover date and continue through the data point for the 8th month immediately after the changeover date. Each of these 10 data points is the median of 63 monthly totals of health dangerous behaviors. They show that the GED or GED-4 caused an immediate drop in the frequency of the behavior. The average (median) total made an immediate decrease in frequency by a factor of 9 when the GED/GED-4 was introduced. Exhibits 229, 230, 231, and 232 are similar summary charts for the behaviors of aggression, destruction, noncompliance and other major disruptive behaviors. In each case there was an immediate drop in frequency that was different in each case. The "jump downs" we see in Exhibits 228 through 231 are summarized in Exhibit 233, which shows that the average (median) jump-down was ÷ 9 (range ÷6 to ÷20).

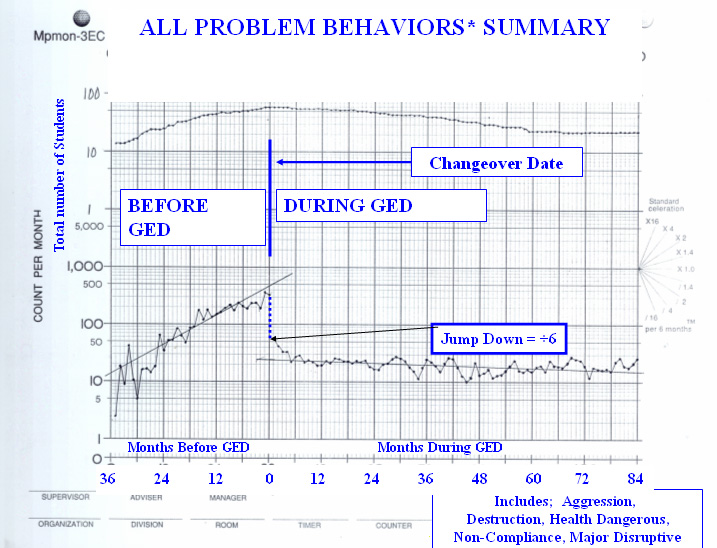

Exhibit 234 is a summary chart that combines all five of the behavior categories that are summarized in Exhibits 229 - 232 into one category called "All Problem Behaviors." This, like the individual summary charts, is a chart in which data is synchronized on the date at which the changeover to the GED or GED-4 took place. The curve at the top of the chart shows the number of students represented by the data points in the data series at the bottom of the chart. The most useful data points to look at are those in which all 63 students are included. For this chart that means the 2 data points immediately to the left of the changeover date, and the 4 data points immediately to the right of the changeover date. This data shows that the GED/GED-4 caused the median of monthly totals for all problem behaviors of the 63 students to drop by a factor of 6. It should be noted that each data point in Exhibit 234 represents the collection of a tremendous amount of behavioral data. For example, the data point to the right of the changeover date represents 24 hours of data collection on 30 days for 5 different behaviors for 63 students. This amounts to 226,800 hours of data collection.

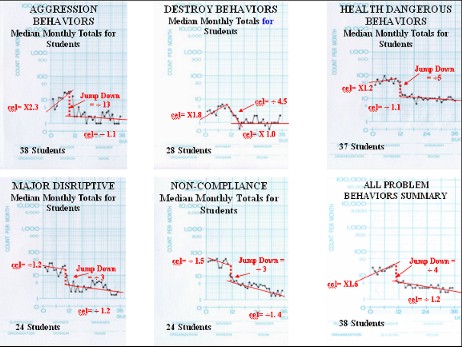

Examining changes in trends as well as jump-downs using summary data from identical groups of students, 1990 to 2001. In order to examine changes in trends with charts such as we have been using, that are synchronized around the changeover date, we need to find groups of students for whom we have data for all of those students for a certain number of months before the changeover date and for whom we have data for all of those students for a certain number of months after the changeover date. We have done this in Exhibit 235. For example, the first chart of Exhibit 235 shows data for aggression for 38 students who attended JRC during the period 1990 to 2001. For each of these 38 students we have data for their 10 months prior to the changeover date (to GED/GED-4) and for their 25 months after the changeover date. Looking at the data for these 38 students only, we see that the frequency of aggression showed an accelerating trend prior to the GED/GED-4, multiplying by a factor of 2.3 every six months. Introduction of the GED caused the frequency to make an immediate jump-down, dividing by a factor of 13. It also caused the trend to change from its previous acceleration of x 2.3 to a deceleration of ÷ 1.3 (i.e., dividing by a factor of 1.3 every six months). The other charts in Exhibit 235 show the changes in celeration for Destroy, Health Dangerous, Major Disruptive, Noncompliance, and All Problem Behaviors (combined), respectively. The All Problem Behaviors chart is one of the best overall summaries of our GED experience during the period from 1990 to 2001. It shows that the combined total of all problem behaviors was increasing--multiplying by a factor of 1.6 every six months--prior to the use of the GED. When the GED was introduced, it caused an immediate drop in frequency by a factor of 4 and subsequently caused a further steady decrease in which the frequency divided by a factor of 1.2 every 6 months thereafter.

Use of GED with Higher Functioning Students Starting in 1998, we began an increasing use of the GED in the treatment of some of our "higher functioning" students-students who have behavioral or psychiatric problems, as distinguished from autistic-like students. Exhibit 236 is a list of the types of diagnoses or educational categories that tend to be assigned to these higher functioning students. Currently, approximately 37% of the JRC population have these diagnoses or educational labels.

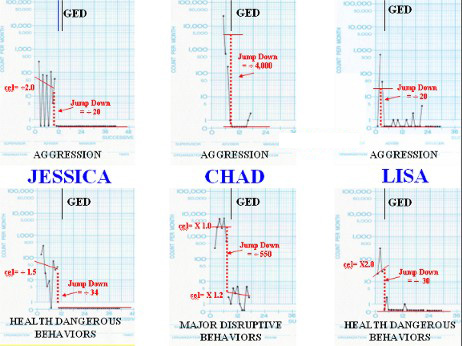

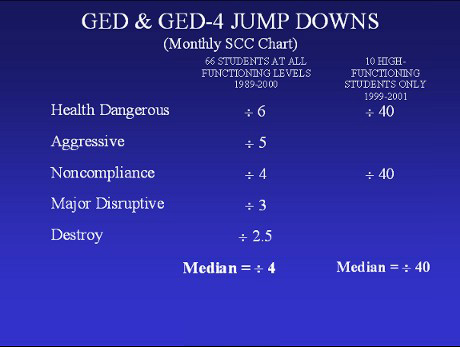

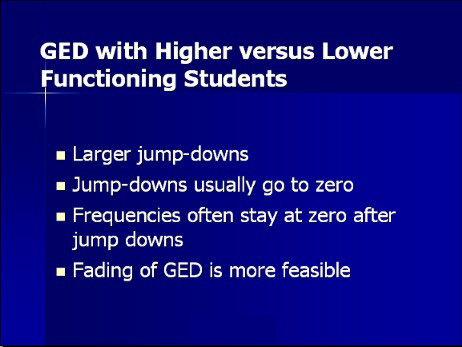

We have found that the GED appears to be much more effective with these higher functioning students. The jump-downs are much greater and the jump-downs are often to the zero line. Exhibits 237 and 238 show individual charts for two behaviors each of 6 different students. In each case the two behaviors shown are aggression and health dangerous behaviors. Notice that the jump-down shows ranges from ¸16 to ¸4,000 with a median jump-down of ¸32 (average of the low median of ¸30 and the high median of ¸34).

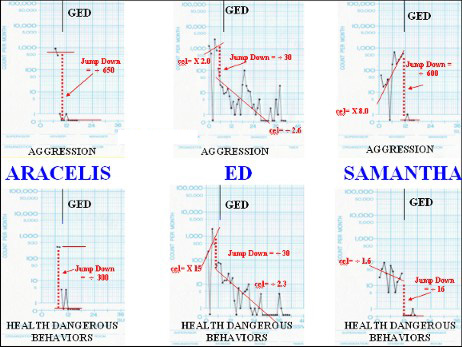

Exhibit 239 is a summary chart for the aggressive behaviors of all 10 higher functioning students during the years 2000-2001. This is another synchronized summary chart. The heavy vertical line in the middle of the chart shows the changeover date on which the students were started on the GED. Data points to its right are for the median of the monthly totals on the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc. months after starting GED treatment. Data points to its left are for the median monthly totals on the 1st, 2nd, 3rd etc. months before starting GED treatment.

The number of students whose data contributes to the median monthly totals shown in the data series at the bottom of the chart is shown in the curve at the top of the chart. For evaluating the jump-down we need to look at the two data points that represent the same group of students. These are the data point immediately before the change to GED and the data point immediately after the change to the GED. The jump-down between these two points is ¸40. Exhibit 240 compares the jump-downs for aggressive and health dangerous behaviors of this group of ten higher functioning students in 1999-2002 with the jump-downs for aggressive and health-dangerous behaviors for 66 students at all functioning levels (most of whom were at lower functioning levels) during 1989-2000. As the table shows, the average (median) jump-down in the case of the higher functioning students was ten times greater.

In summary, the GED seems to be more effective with higher than with lower functioning students for the following reasons (Exhibit 241):

Because of GED's greater effectiveness with the higher functioning than with lower functioning students, we have been more successful in fading the device with high functioning students than with low functioning ones. Discoveries or Conjectures Our experience with SIBIS and GED has led us to the following findings or conjectures regarding the use of skin shock. (See Exhibits 242 though 245).

Exhibit 246 shows web sites where additional information may be obtained.

|