|

Use of Skin-Shock at the Judge Rotenberg Educational Center (JRC) |

IS THE BEHAVIORAL PROGRESS MADE AT JRC

SUSTAINABLE AND GENERALIZABLE?

A FOLLOW-UP STUDY OF FORMER JRC STUDENTS

Peter E. Jaberg, Andre Vlok, Joseph Assalone, Rosemary Silva, and Matthew L. Israel, Ph. D.

Judge Rotenberg Educational Center

Canton, MA USA

This study examines the post-treatment outcomes of 49 former students of the Judge Rotenberg Educational Center (JRC), a residential care facility that employs a highly consistent application of behavioral treatment and educational programming. The students were evaluated after having left JRC for an average (mean) of 1.9 years (range 0.5 to 4.5 years). A subjective General Life Adjustment rating (obtained from guardians and former students) and objective counts of certain Quality of Life Indicators. The group of students as a whole showed marked improvement over their status prior to enrolling in JRC on the measures employed.

Introduction

Examining post-treatment patient or student outcomes for the users of residential care facilities remains an important aspect in assessing the long-term durability of the treatment students receive while in the care of the facility, as well as the generalizability of treatment effects to natural environments. The participants in this study consisted of former students of the Judge Rotenberg Educational Center (JRC). JRC operates day and residential programs for children and adults with behavior problems, including conduct disorders, emotional problems, brain injury or psychosis, autism and developmental disabilities. This study is part of JRC’s on-going efforts to assess the effectiveness of treatment after students have left the program.

The basic underlying approach taken in all of JRC's programs is the use of behavioral psychology and its various technological applications, such as behavioral education, programmed instruction, precision teaching, behavior modification, and behavior therapy and counseling. From JRC's inception, its basic philosophy has always included the following principles: a willingness to accept students with the most difficult behavioral problems and a refusal to reject or expel any student because of the difficulty of his or her presenting behaviors; the use of a highly structured, consistent application of behavioral psychology to both the education and treatment of its students; a minimization of the use of psychotropic medication; and the use of the widest range of effective behavioral education and treatment procedures available1. As a result of JRC’s zero-rejection admissions policy, students who attend JRC have included some of the most challenging and difficult students in the nation. A typical JRC student comes into the facility taking one or more psychotropic medications (over 90% of incoming students are on at least one psychotropic medications—medications with serious side effects), has failed in four previous special education settings, has extremely poor interpersonal relationships with others (including family members), and was likely on a trajectory to end up in a psychiatric hospital or prison. Indeed, many students have a history of psychiatric hospitalizations prior to admission and some have been referred to JRC form a prison setting.

Method

Participants

The participants consisted of 49 former students of

the Judge Rotenberg Educational Center (JRC). Out of an initial pool of 417

former students, 145 were selected to be contacted for data collection. The

criteria for the selection of the 145 former students included: a) they attended

JRC for at least 6 months; b) they have been away from JRC for at least 6

months; c) they are still alive and have valid contact information available; d)

they had agreed to participate in previous editions of this study.

From this selected sample of 145 students, data had all ready been collected in the previous year’s edition of this study for 15 former students. Data were successfully collected this year for an additional 34 (26%) of the remaining 130 former students selected for this years study. All together, data was successfully collected for a third (34%) of the selected sample.

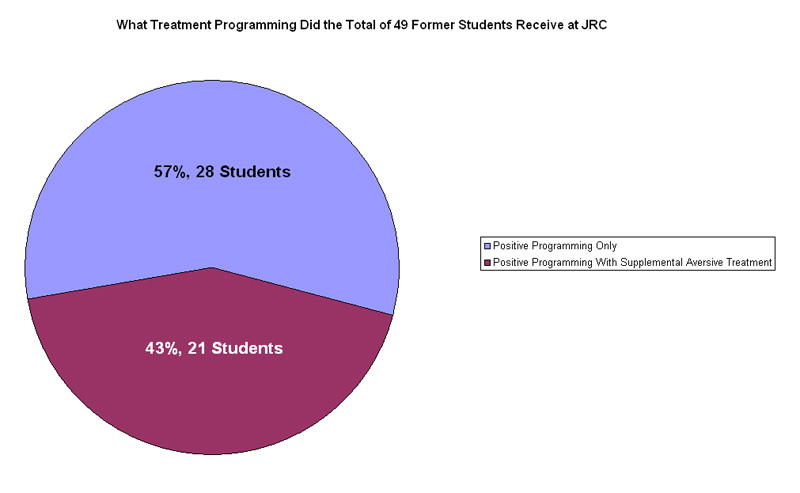

All of the former students included in this study (i.e., the 49 for whom data was collected last year and this year) had received comprehensive behavioral treatment during their tenure at JRC. For 28 of these former students (57%), treatment had consisted of positive-only programming. For 21 of these former students (43%), treatment had consisted of positive programming supplemented with contingent aversives in the form of a brief skin shock generated by the Graduated Electronic Decelerator (GED) device2. Please see Figure 1.

Figure 1

Method

Once potential participants were identified using the selection criteria

described above, the legal guardian of the participant, a family member, or the

former student himself or herself was contacted by telephone by a JRC staff

member. During a telephone interview, the respondents were asked a set of

questions from a structured questionnaire, which included questions regarding

current dimensions of general life functioning including psychiatric

hospitalizations, psychotropic medications, legal involvement, day-time

activities and employment status, educational activities, and recreational

activities. Guardians were also asked to provide a general narrative and

comments regarding the former students’ performance and to provide a rating of

their general life adjustment based upon a 5-point Likert-type scale (with

1-very poor, 2-below average/not good, 3-fair, 4-good, and 5-exceptional). These

ratings were provided both for present life adjustment and for life adjustment

prior to receiving treatment at JRC.

Results

From an initial total pool of 145 potential participants, 49 (34%; including data collected both this year and in 2006) guardians, family members, or former students were successfully contacted As has been the case with the previous JRC follow up studies, the sole reason for inability to contact participants was a lack of current contact information despite genuine efforts to maintain contact and obtain current contact information (e.g., repeated phone contacts, searches of information databases such as 411 or Whitepages, etc.).

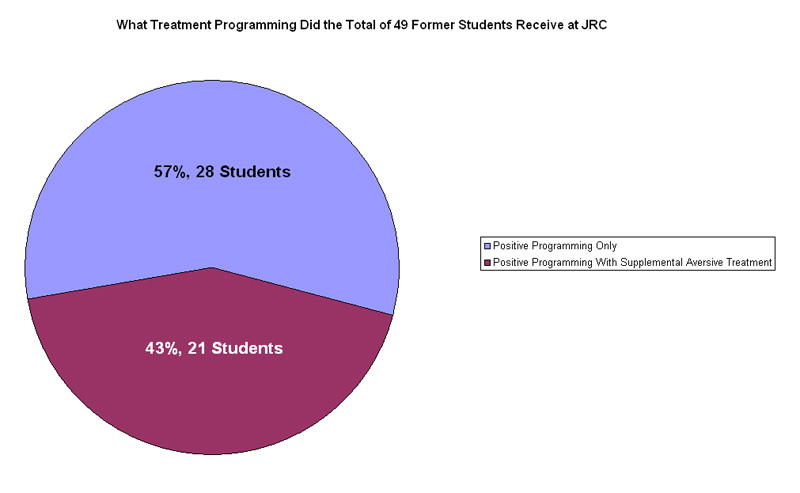

The mean age of the former students (i.e., at the time of this investigation) was 20.8 years with a range of 9.6 to 25.6 years of age. The mean length of stay at JRC was 2.5 years with a range of .6 to 7.4 years. The mean time since discharge from JRC was 1.9 years with a range of .5 to 4.5 years. The reporter was a mother or father (either by birth or adoption) in 25 (51%) of the cases, the participant them self in 14 (29%) of the cases, and another extended family member in 7 (14%) of the cases (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Living/Residential Situation

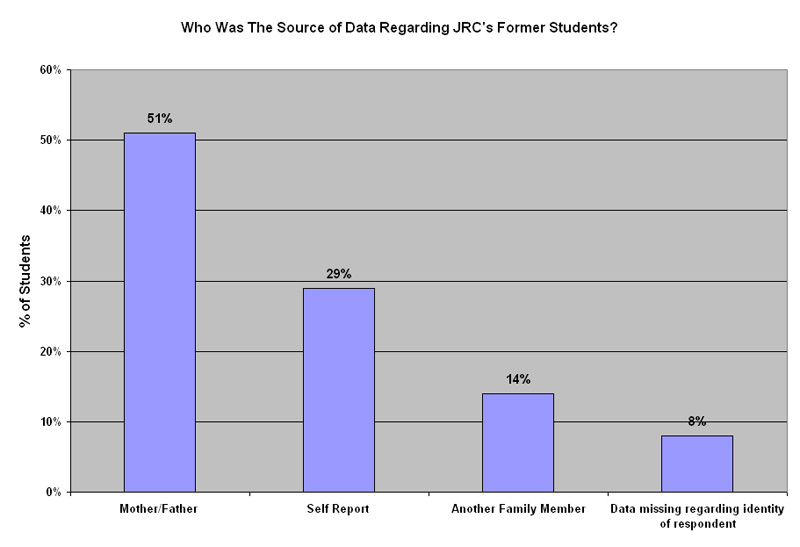

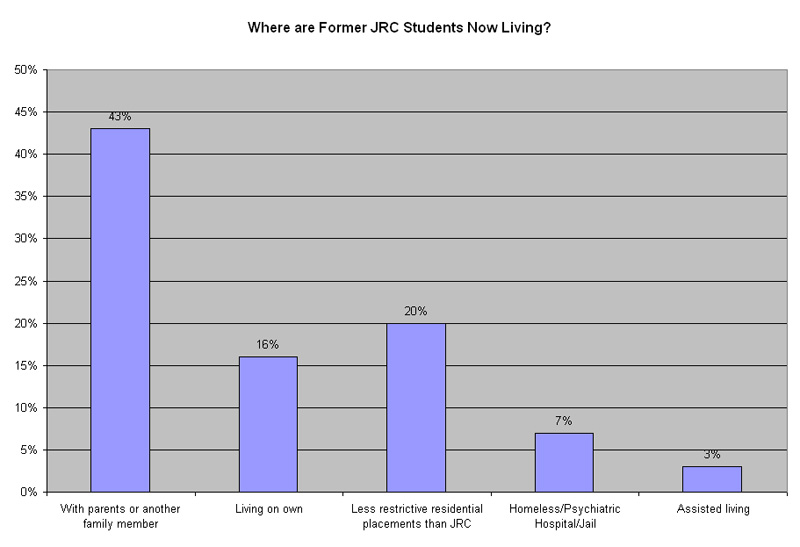

Where are former JRC students living? The analysis of the former students’ living situation following their treatment at JRC shows (see Figure 3) that 59% of the former students were either living in their family’s residence (43%) or independently on their own (16%), 20% were in less restrictive residential placements (less restrictive than JRC). 7% were either homeless or in a psychiatric hospital, or in jail and 3% were utilizing assisted living services.

Figure 3

Treatment

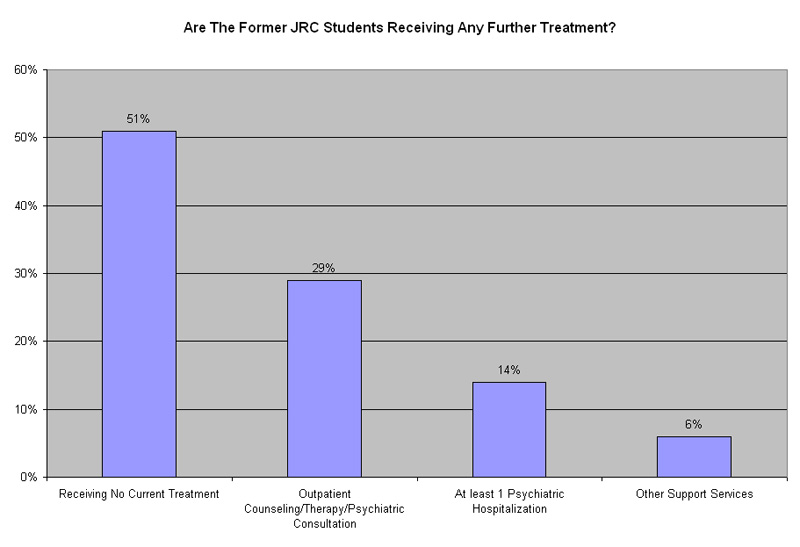

What are the ongoing treatment needs of students after leaving JRC? As is shown in Figure 4, Fifty-one percent of the former students no longer needed nor utilized any ongoing treatment resources at the time of the study follow-up, 29% utilized outpatient counseling, therapy, or psychiatric consultation and 14% of the former students required at least one psychiatric hospitalization and 6% other support services.

Figure 4

Psychotropic Medications

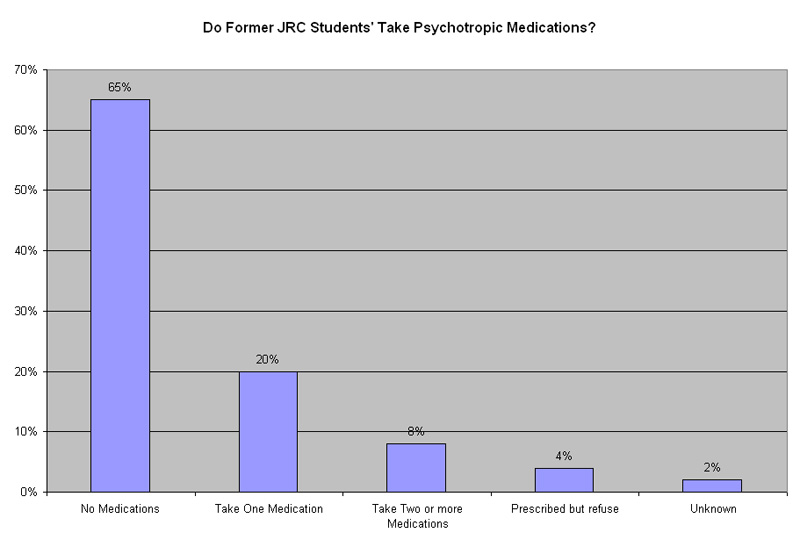

Is there a continuing need for the use of medications following JRC treatment? As is shown in Figure 5, 65% of the former students were free of any psychotropic medications at the time of follow up and 32% of former students had been restarted on psychotropic medications since discharge (compared to over 90% at the time of JRC admission).

Figure 5

Education

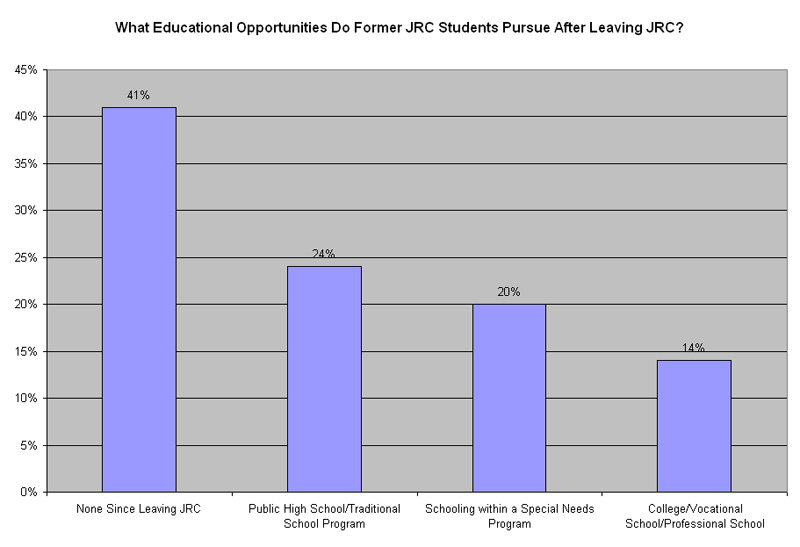

What impact does JRC’s program have on educational functioning? Although, as is shown in Figure 6, the number of students receiving no educational services is a sizable minority of the sample (41%; some of these students have aged out of the educational system and have not pursued further education), there are also a number of students that have successfully continued their education beyond JRC. Currently, 24% of the former students are in public or traditional school settings and 14% are pursuing college, vocational, or professional training. Some (20%) of the former students of traditional school age have continued to receives residential or special educational services (i.e., in less restrictive settings reflecting the improved safety of their behavior).

Figure 6

Employment

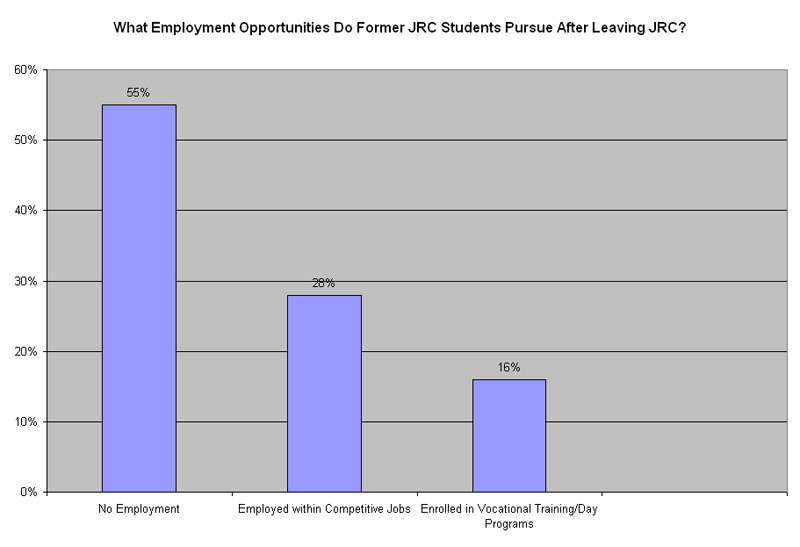

Fifty-five percent of the former students are not currently employed (see Figure 7). Part of this can be explained by the age of the former student. That is, it is not necessarily reasonable to expect school-age individuals to be working. Also, many of JRC’s former students have development or physical disabilities that might limit their employability. All of that being said, most of JRC’s students enter the program demonstrating behaviors that would prevent them from maintaining any gainful employment (in addition to the previously mentioned developmental impairment). Of the remaining 45% of the former students included in this study, 28% were employed in competitive jobs and 16% were enrolled within vocational training/day program settings.

Figure 7

Recreation

The former students reported a wide range of interests and hobbies including: playing basketball, weight lifting, riding roller blades, bicycling, riding motorcycle, taking walks, going to the park/beach, swimming, watching television, playing video games, going out to eat, hanging out with friends, going bowling, reading the newspaper, listening to music, surfing the internet, and spending time with their families. As is discussed in the two sections below, the demonstration of inappropriate behaviors prior to the students’ enrollment in JRC interfered with functioning in all aspects of their daily life, including their ability to engage in recreational activities. It appears now, however, that the former students continue to engage in a wide range of recreational activities in their personal life.

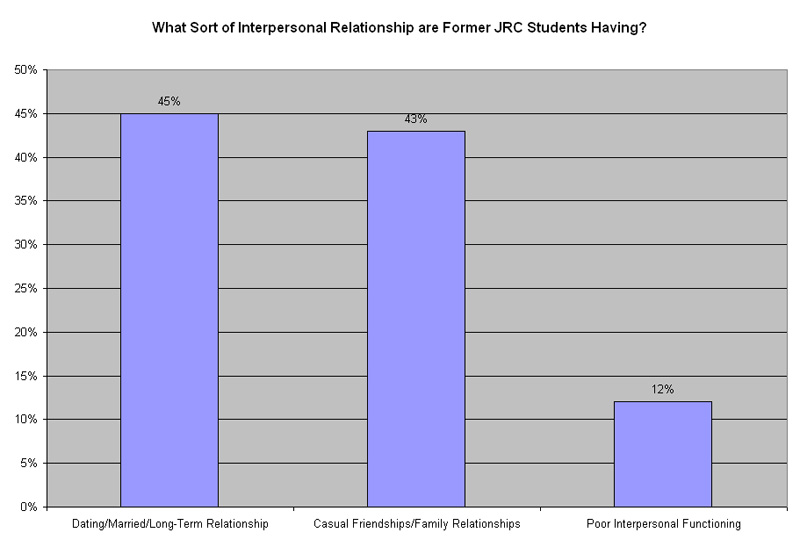

Relationship Functioning

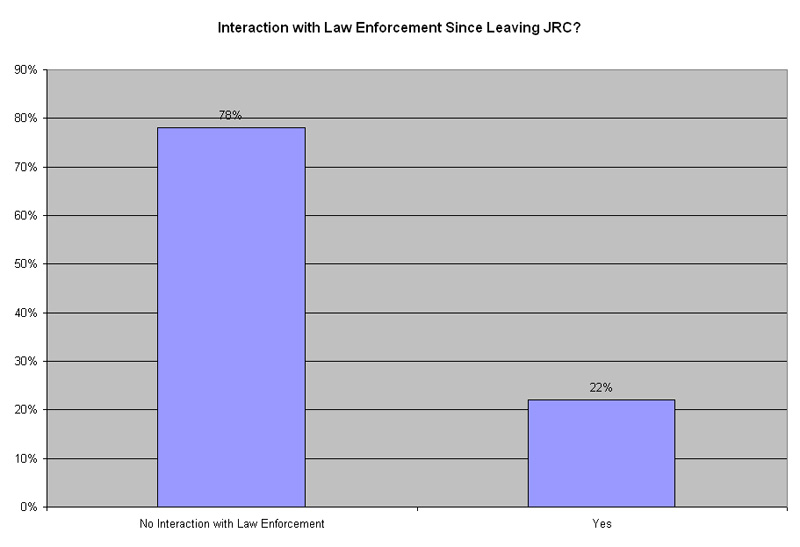

This area of functioning is typically difficult to quantify. There is likely a bias to report more troublesome aspects of relationship in a report than to focus on positive relationship aspects. When asked directly about meaningful relationship and dating, 45% reported that they were either married, in a long-term relationship, or consistently dating (see Figure 8). This datum is remarkable to the extent that it was these very close relationships that the typical student admitted to JRC were not able to enjoy prior to admission to JRC due to the extreme disruptiveness of their inappropriate behaviors. Another 43% reported some enjoyable casual friendships or family relationships. Only about 12% reported a severe a lack of ability to enjoy or effort toward building interpersonal relationships. As is shown in Figure 9, about 22% of the former students continued to have interpersonal/social problems to the point that law enforcement was required to intercede. The majority of former students managed to engage in socially appropriate behavior such that no intercession by law enforcement was required.

Figure 8

Figure 9

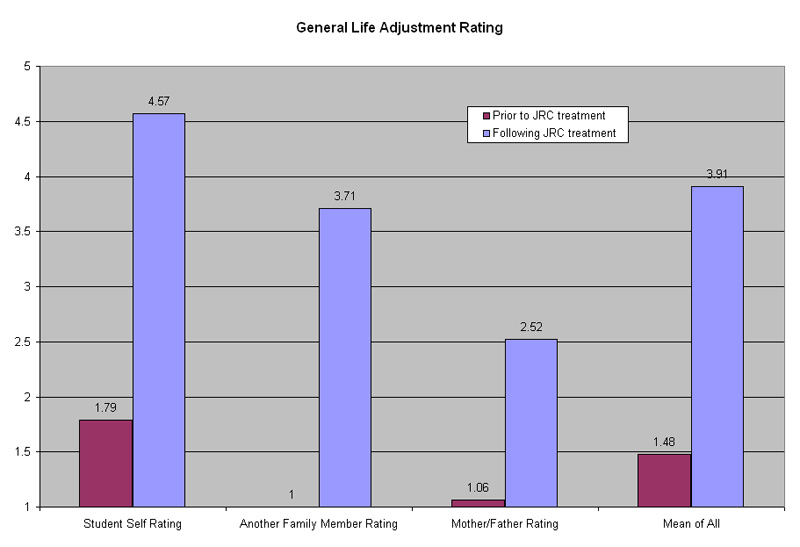

General Life Adjustment Rating

See Figure 10 for comparisons of general life adjustment (GLA) ratings (by mother/father, self, or another family member) before and after JRC. These subjective ratings are vulnerable to a number of report biases, but do reflect a genuine perception of the respondents that the participant’s overall level of functioning has continued at an improved level since discharge from JRC.

Figure 10

Discussion

The results of this investigation indicate that former students of JRC demonstrated marked improvement in their life adjustment and quality of life following treatment. These findings are consistent with follow-up studies from four previous years.

The marked improvement, as indicated by the data for these former students, serves as evidence that not only have indicators for quality of life ostensibly improved since starting treatment at JRC, but that this improved functioning has continued for as long as 4.5 years after the former student was discharged from JRC. After leaving JRC, students from this study transitioned back home, to another less restrictive residential program, or to a day educational/vocational program. Some of these students started full or part time jobs and some pursued further (post-secondary) education. For others, to be able to safely return home and have relatively normal family and peer relationship is an indicator of treatment success.

Limitations of the current study include an absence of formal/reliable data (beyond retrospective informant report) of the student’s functioning prior to admission. Rather, typical admission status is often referred to in this study as a basis for comparing their current post-treatment functioning. Further, as with previous follow-up studies conducted at JRC, there was relatively high attrition due to the inability to locate current contact information for a significant number (66%) of the initially selected participant pool. The ability to successfully contact the guardians of former students remains a significant aspect in assessing the long-term treatment effects of residential programs. Maintaining more frequent on-going contact with guardians of former students, as well as the former students themselves, may increase the ability to track the follow-up progress of more students in the future.

Suggested areas of improvement that might be considered to enhance future follow-up studies of residential care include the following additions: (1) a standardized symptom or behavioral checklist administered at pre-admission, at discharge, and at specified periods post-discharge; (2) a control group consisting of students accepted into the facility, but not attending; (3) an examination of the relationship of pre-admission variables (e.g., number of previous placements, intellectual functioning, and prior adjudication) to post-treatment outcomes; (4) an examination of the relationship of other variables (such as time since discharge, length of stay, reason for discharge, etc.) to post-treatment outcomes; and (5) further examination of ratings in terms of statistical significance as technologically quantifiable.

In conclusion, although there were several factors that limited the generalizability and significance of the findings, the results indicate that former students of the Judge Rotenberg Educational Center showed substantial overall improvement as measured by the indicators of quality of life as used in this study.

Table of Positive Results

| 51% are receiving no further treatment |

| 65% Now free of medication |

| 24% in Public School |

| 14% now in College or Vocational school |

| 83% have good interpersonal relationships |

| 78% have had no contact with legal system |

| Quality of life improved from a rating of 1.5 to 3.9 out of 5.0 |

[1] Additional information is available from JRC’s website at www.judgerc.org.

[2] The GED is a remote-controlled skin-shock device which delivers brief, mild electrical stimulation to the surface of the skin. The reader is referred to www.effectivetreatment.org/remote.html for a detailed paper regarding the development and characteristics of the GED. Additionally, a case study documenting the effectiveness of positive programming supplemented with contingent aversives in the form of the GED can be found at www.effectivetreatment.org/treat.html.