|

Use of Skin-Shock at the Judge Rotenberg Educational Center (JRC) |

COMPARING THE USE OF SAFMEDS AND COMPUTERIZED FLASHCARDS

Jill E. Hunt, Michelle I. Harrington, and Matthew L. Israel, Ph.D.

Judge Rotenberg Educational Center

Canton, MA USA

The Judge Rotenberg Educational Center (www.judgerc.org) operates day and residential programs for children and adults with behavior problems, including conduct disorders, emotional problems, brain injury or psychosis, autism, and developmental disabilities. The fundamental approach taken at JRC is the use of behavioral psychology and its various technological applications, including behavioral education, programmed instruction, precision teaching, behavior modification, behavior therapy, behavioral counseling, self-management of behavior, and chart-sharing.

Participants in this study worked through a series of lessons designed to teach the Periodic Table of Elements and the abbreviation for each element. The curriculum was presented using SAFMEDS, as well as the computer, using proprietary JRC software. This curriculum was designed using the tenets of Precision Teaching (Binder, Watkins, 1990). Lessons followed a varied sequence, and material was broken up into small steps that had to be mastered at a pre-set rate correct per minute before moving on to the next lesson. We examined the participant’s pre-test and post-test scores, as well as the time it took them to complete the lessons both pre and post-test. Also examined was the difference in using a SAFMEDS curriculum and computer curriculum, to include time spent developing the curriculum and differences in student progress.

Methods

Participants and Setting

There were 8 participants in this study, 6 males and 2

females. Their ages ranged from 14.5 to 20.10 years, with diagnosis including;

ADHD, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Mood Disorder and Bipolar Disorder. All

participants attended school at the Judge Rotenberg Center and lived in one of

JRC’s group homes.

These participants were chosen because they were all

reading at approximately the same level, within a range of two years.

Participants were located in 5 different classrooms throughout the school during

the academic day, from 9AM to 3PM, Monday through Friday. Half of the

participants used a computer that was individually configured to meet both their

behavioral and academic needs, including immediate student-specific feedback for

correct and incorrect answers. The remaining half of the students used SAFMEDS

and received verbal feedback for both correct and incorrect responses at the end

of the timing cycle.

Measures and Instruction

Half of the participants worked on the JRC proprietary

software, Just the Facts, and the other half of the students used SAFMEDS.

Lessons were broken down into small curriculum-steps comprised of new material

and reviews. Each step included 10 new elements and each review was built off of

previous lessons. Each participant was required to complete ten 30-second

timings per day. Participants using the computer were required to complete

See/Type timings. During the timing, the participant could hit a specific key to

request a visual prompt of the answer. Prompts included the initial letter(s),

of the element, and for each additional time the prompt request key was hit,

another letter of the answer appeared. Participants using SAFMEDS were required

to complete See/ Say timings. The participants were required to answer problems

at an individualized rate correct to move from lesson to lesson.

All data was plotted on a Standard Celeration Chart, which showed correct responses, incorrect responses, prompts and the time it took to complete a cycle. (Lindsley, 1992) A cycle was defined as a certain number of problems, a certain number of correct responses or by a pre-set or pre-determined amount of time.

Participants received feedback for both correct and incorrect responses. When the student entered a correct response, a green check appeared on the screen and when an incorrect response was entered, a red X appeared on the screen. They also received a set amount of points for lesson completion, which could be exchanged for a break, use of their headphones, items in the behavior boutique, or computer games at the end of each day.

Results

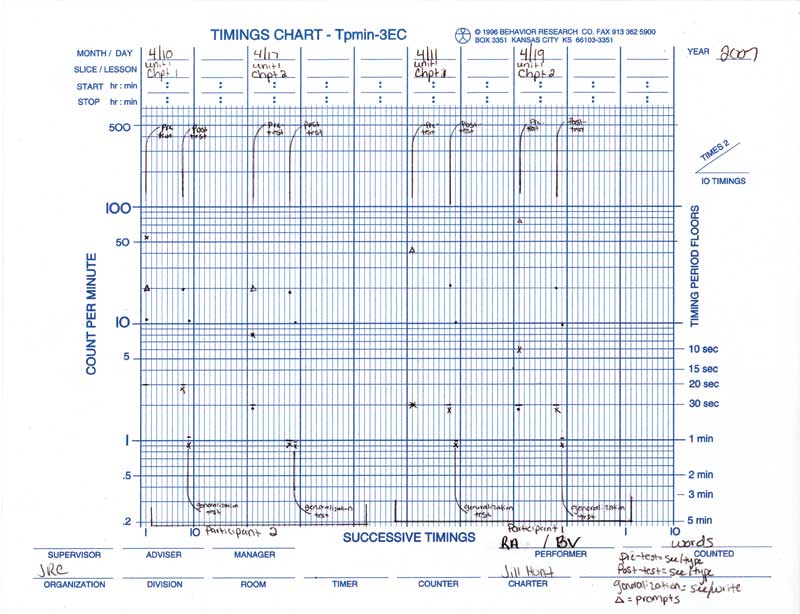

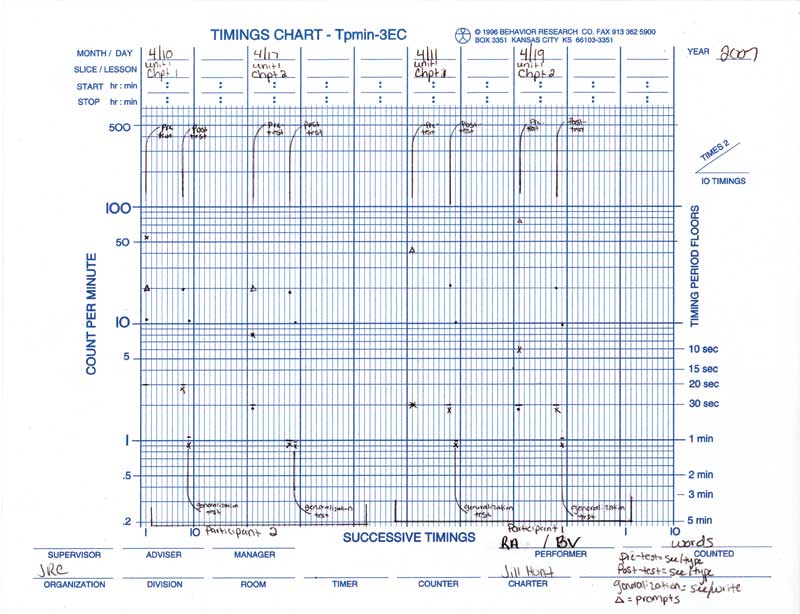

Participant One (See Figure 1), RA, initially completed the timings using the computer curriculum. She saw the abbreviation and typed the corresponding element. To check for generalization, she was switch to SAFMEDS of the same material, using the See/Write learning channel. For the first chapter she completed, RA’s pre-test scores were 2 correct and 2 incorrect responses with 44 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, she made 22 correct, 0 incorrect responses and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, she made 10 correct and 0 incorrect, with 0 prompts in a 65 second timing. For the second chapter, pre-test scores were 0 correct and 6 incorrect responses with 78 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, she made 20 correct, 0 incorrect responses and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, she made 10 correct and 0 incorrect responses, with 0 prompts in a 63 second timing.

Participant Two (See Figure 1), BV, initially completed the timings using the computer curriculum. He saw the abbreviation and typed the corresponding element. To check for generalization, he was switched to SAFMEDS of the same material, using the See/Write learning channel. For the first chapter he completed, BV’s pre-test scores were 12 correct and 54 incorrect responses with 20 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, he made 20 correct and 0 incorrect responses and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, he made 10 correct and 0 incorrect responses, with 0 prompts in a 65 second timing. For the second chapter his pre-test scores were 0 correct and 8 incorrect responses with 20 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, he made 20 correct, 0 incorrect responses and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, he made 10 correct and 0 incorrect responses, with 0 prompts in a 57 second timing.

Figure 1

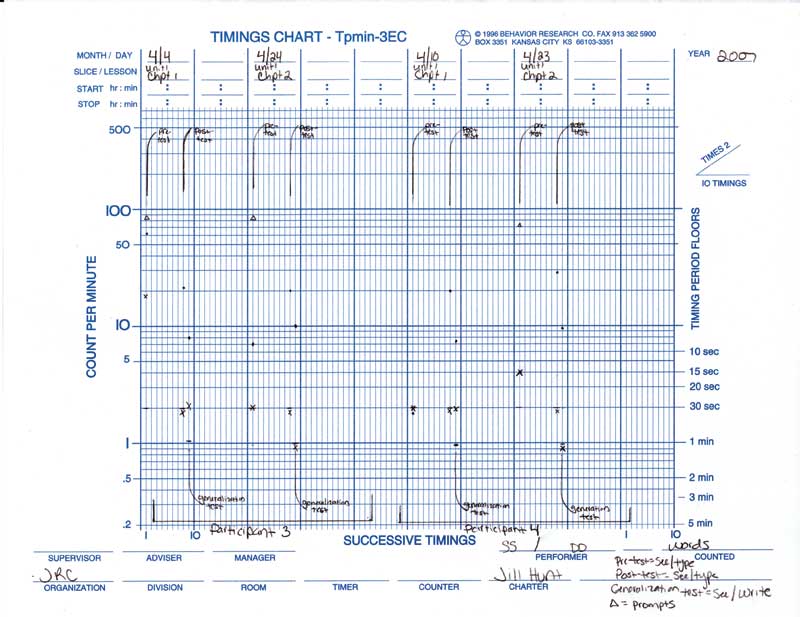

Participant Three (See Figure 2), SS, initially completed the timings, using the computer curriculum. She saw the abbreviation and typed the corresponding element. To check for generalization, she was switched to SAFMEDS, of the same material, using the See/Write learning channel. For the first chapter she completed, SS’s pre-test scores were 67 correct and 16 incorrect responses with 87 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, she made 40 correct, 0 incorrect responses and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, she made 8 correct and 2 incorrect responses, with 0 prompts in a 57 second timing. For the second chapter her pre-test scores were 7 correct and 2 incorrect responses with 89 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, she made 20 correct, 0 incorrect responses and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, she got 10 correct and 0 incorrect responses, with 0 prompts in a 60 second timing.

Participant Four (See Figure 2), DD, initially completed the timings using the computer curriculum. He saw the abbreviation and typed the corresponding element. To check for generalization, he was switched to SAFMEDS, of the same material, using the See/Write learning channel. For the first chapter he completed, DD’s pre-test scores were 1 correct and 2 incorrect response with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, he made 20 correct, 0 incorrect responses and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, he got 8 correct and 2 incorrect responses, with 0 prompts in a 65 second timing. For the second chapter his pre-test scores were 4 correct and 4 incorrect responses with 74 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, he made 15 correct, 0 incorrect and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, he made 10 correct and 0 incorrect responses, with 0 prompts in a 65 second timing.

Figure 2

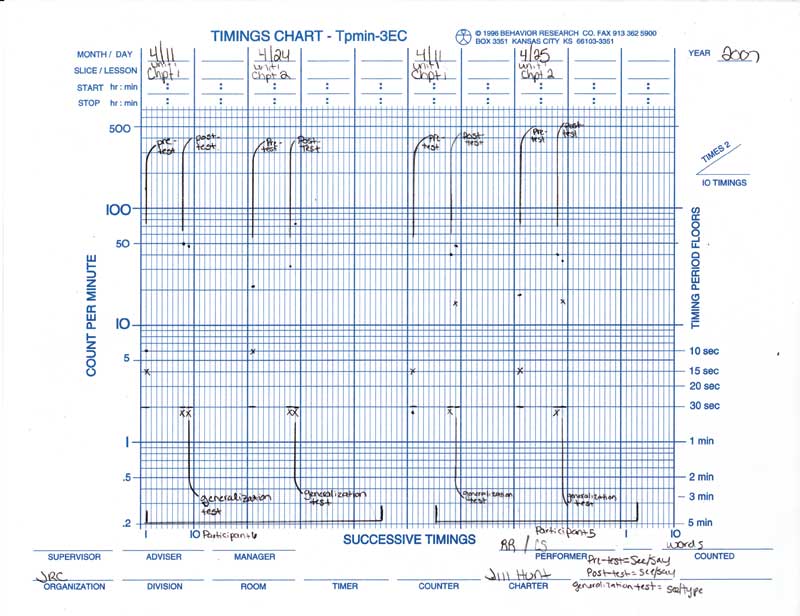

Participant Five (See Figure 3), CS, initially completed the timings using SAFMEDS curriculum. She saw the element and said the corresponding abbreviation. To check for generalization, she was switched to the computer curriculum, of the same material, using the See/Type learning channel. For the first chapter she completed, CS’s pre-test scores were 0 correct and 10 incorrect responses with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, she made 40 correct, 0 incorrect responses and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, she made 22 correct and 8 incorrect responses, with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the second chapter she completed her pre-test scores were 8 correct and 4 incorrect responses with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, she made 40 correct, 0 incorrect responses and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, she made 18 correct and 7 incorrect responses, with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing.

Participant Six (See Figure 3), RR, initially completed the timings using SAFMEDS curriculum. He saw the element and said the corresponding abbreviation. To check for generalization, he was switched to the computer curriculum, of the same material, using the See/Type learning channel. For the first chapter RR’s pre-test scores were 6 correct and 4 incorrect responses with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, she made 50 correct, 0 incorrect responses and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, he made 24 correct and 0 incorrect responses, with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the second chapter he completed his pre-test scores were 12 correct and 4 incorrect responses with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, he made 48 correct, 0 incorrect responses and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, he made 42 correct and 0 incorrect responses, with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing.

Figure 3

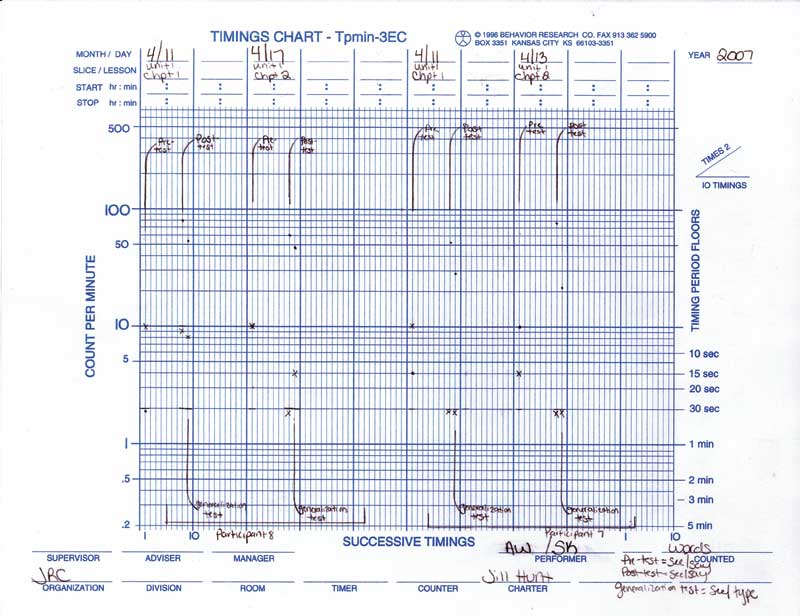

Participant Seven (See Figure 4), AW, initially completed the timings using SAFMEDS curriculum. He saw the element and said the corresponding abbreviation. To check for generalization, he was switched to the computer curriculum, of the same material, using the See/Type learning channel. For the first chapter AW’s pre-test scores were 2 correct and 10 incorrect responses with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, he made 60 correct, 0 incorrect responses and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, he made 28 correct and 0 incorrect responses, with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the second chapter his pre-test scores were 10 correct and 4 incorrect responses with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, he made 80 correct, 0 incorrect responses and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, he made 18 correct and 0 incorrect responses with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing.

Participant Eight (See Figure 4), SK, initially completed the timings using SAFMEDS curriculum. He saw the element and said the corresponding abbreviation. To check for generalization, he was switched to the computer curriculum, of the same material, using the See/Type learning channel. For the first chapter SK’s pre-test scores were 0 correct and 10 incorrect responses with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, he made 60 correct, 0 incorrect responses and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, he made 24 correct and 4 incorrect responses, with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the second chapter he completed his pre-test scores were 10 correct and 10 incorrect responses with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. When post-tested, he made 60 correct, 0 incorrect responses and used 0 prompts in a 30 second timing. For the generalization test, he made 60 correct and 4 incorrect responses, with 0 prompts in a 30 second timing.

Figure 4

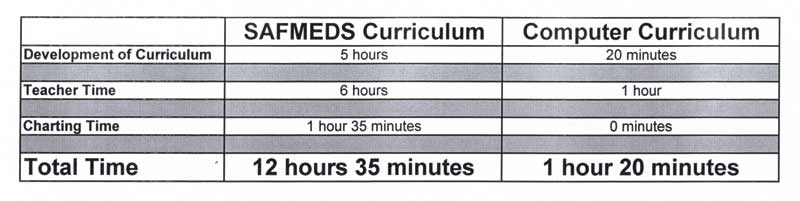

The development of SAFMEDS was extensive when compared to the amount of time needed to create the computer program. It took 5 hours to create the SAFMEDS and to separate them into the appropriate chapters, while creating the computer program it took 20 minutes to enter the data and separate it into chapters. The SAFMEDS also took up a large amount of teacher-time, as the teacher had to complete timings with the participants, and prompt them to keep their materials neat and organized. In addition, the participants often lost the SAFMEDS and new SAFMEDS needed to be created. At times, the participants would forget to complete the timings, if they were not prompted to do so. In comparison, teacher time spent with those participants on the computer program was 45 minutes total over the course of the project. The teacher would simply check the scores of the participants and insure they completed their timings; less feedback was needed as the computer gave immediate feedback to each participant. Participants using the computer required less prompts to complete timings and would often complete more than the required amount of timings each day. In comparing the amount of time it took to chart the data, it was found to take 1 hour and 35 minutes to chart all SAFMEDS data across the study, while the computer program charted automatically. In both cases, the teacher ensured they were given their rewards at the end of each day. Participants reported liking the computer curriculum more, based on ease of access. They did not have to keep track of any physical items and enjoyed working on the computer more.

Discussion

Data shows that both types of curriculum were effective. Participants were able to learn and retain the material presented, whether they used the computer curriculum or the SAFMEDS curriculum. The material also generalized for both types of curriculum. The difference between the two curriculums was the amount of time needed to develop, implement and run the academic programs. Clearly shown in Figure 5 is that the SAFMEDS curriculum took 89 percent more time overall. Use of a computer curriculum allows the teacher to spend more time on instruction and allows participants to progress at a faster rate. Further study could examine long term retention rates of both SAFMEDS and the computer curriculum and other types of material to be learned.

Figure

5

References

Binder, C., & Watkins, C. L. (1990), Precision Teaching and Direct Instruction: Measurably superior instructional technology in schools. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 3 (4), 74-96.

Lindsley, O.R., (1992). Precision Teaching: Discoveries and effects. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25, 51-57