|

Use of Skin-Shock at the Judge Rotenberg Educational Center (JRC) |

USING A PRECISION TEACHING SOFTWARE TO TEACH

LETTER MATCHING AND

ASSOCIATION SKILLS OF UPPERCASE AND LOWERCASE LETTERS

Michelle I. Harrington, Angela Galvin, Edward Langford, and Matthew L. Israel, Ph.D.

Judge Rotenberg Educational Center

Canton, MA USA

The Judge Rotenberg Educational Center (www.judgerc.org) operates day and residential programs for children and adults with behavior problems, including conduct disorders, emotional problems, brain injury or psychosis, autism, and developmental disabilities. The fundamental approach taken at JRC is the use of behavioral psychology and its various technological applications, including behavioral education, programmed instruction, precision teaching, behavior modification, behavior therapy, behavioral counseling, self-management of behavior, and chart-sharing.

Participants in this study worked through a series of lessons designed to teach them the association between uppercase and lowercase letters of the alphabet. The curriculum was presented on a computer, using proprietary JRC software. This curriculum was designed using the tenets of both Precision Teaching and Programmed Instruction. (Binder, Watkins, 1990) Lessons followed a preset sequence and material was broken up into small steps that must be mastered at a preset rate correct per minute before moving onto the next lesson. We examined the participants pre-test and post-test scores and the time it took them to complete the lessons before and after completing all lessons in the curriculum.

Methods

Participants and Setting

There were three participants in this study, two males

and one female. Their ages ranged from 18.4 to 19.5. Diagnoses included Autism

and Pervasive Developmental Disorder. Two participants were not testable for IQ

level and the third had achieved a Full Scale IQ of below 20 based on previous

testing. All participants attended school at the Judge Rotenberg Center and

lived in one of JRC’s group homes.

These participants were chosen because they were able to

recite and identify the letters of the alphabet, but did not understand the

relationship between uppercase letters and lowercase letters. All three

participants were in the same classroom during the academic day, from 9AM to

3PM, Monday through Friday. Each participant used a computer that was

individually configured to meet both their behavioral and academic needs. This

included student specific feedback for correct and incorrect answers, cycle

length and rewards for completing timings.

Measures and Instruction

All participants worked on the JRC proprietary

software Alphabet Skills. They worked through lessons that taught matching

uppercase letters to lowercase letters. Lessons were presented using programmed

instruction. Letters of the alphabet were introduced one by one, with review

lessons following the introduction of each new letter. Each new letter was

introduced following a specific sequence of verbal and visual prompts. The

participant was presented with an uppercase letter, heard the letter name and

either touched with a finger or clicked with a mouse on the corresponding

lowercase letter. Each trial had 5 parts, where first the uppercase letter was

paired with the lowercase letter, then the answer is the only letter that

appears, and with each subsequent part, another distracter letter was added. The

participants were required to answer problems at an individualized rate correct

to move from lesson to lesson.

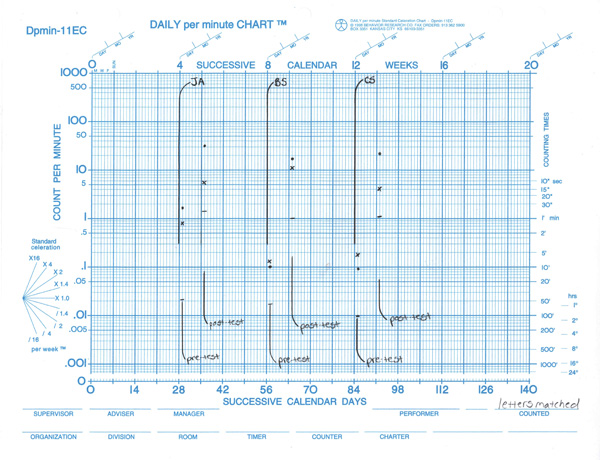

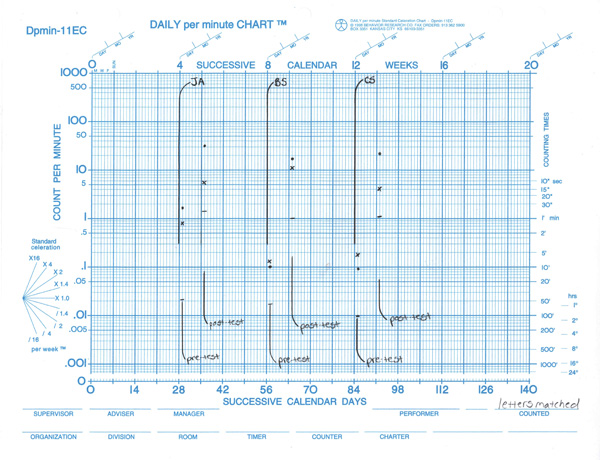

All data were plotted on a Standard Celeration Chart, which showed correct responses, incorrect responses and the time it took to complete a cycle. (Lindsley, 1992) A cycle was defined either by a certain number of problems, a certain number of correct responses or by a pre-set amount of time.

Participants received feedback for both correct and incorrect responses. This feedback was configured to be the most enforcing for the participant, whether it was a specific sound, the screen going black for a preset amount of time or an audio prompt. They also received a tangible reward of their choice at the end of each cycle, which was chosen by the participant, from a reward menu that appeared on the screen at the end of the cycle..

Results

Participant one, JA, completed 12 out of 26 assigned lessons. She became fluent in matching uppercase letters A-L to their corresponding lowercase counterpart at a rate of 15 correct responses per minute. On her initial pre-test, which included all letters of the alphabet, it took JA 47 minutes to answer all questions, equaling a rate of 18 correct and 8 incorrect responses per minute. JA worked on the Alphabet Skills curriculum for 179 days, completing a median of 19 timings per day. When post-tested on all letters, it took JA 38 seconds to go through all letters and she matched them at a rate of 52 corrects and 15 incorrects per minute. (Figure 1)

Participant two, BS, completed all 26 lessons of the program. He became fluent in matching uppercase letters A-Z to their corresponding lowercase counterpart at a rate of 15 correct responses per minute with 0 incorrect. On his initial pre-test, which included all letters of the alphabet, it took BS 62 minutes to answer all questions, equaling a rate of 10 correct and 16 incorrect responses per minute. BS worked on the curriculum for 117 days, completing a median of 16 timings per day. When post-tested on all letters, it took BS 1 minute to go through all letters and he matched them at a rate of 16 corrects and 11 incorrects per minute. (Figure 1)

Participant three, CS, also completed all 26 lessons of the program. He became fluent in matching uppercase letters A-Z to their lowercase counterpart at a rate of 15 correct responses per minute with 0 incorrect. On his initial pre-test, which included all letters of the alphabet, it took CS 107 minutes to answer all questions, equaling a rate of 9 correct and 17 incorrect responses per minute. CS worked on the curriculum for 76 days, completing a median of 12 timings per day. When post-tested on all letters, it took CS 55 seconds to go through all letters and he matched them at a rate of 22 corrects and 4 incorrects per minute. (Figure 1)

Figure 1

Discussion

All participants made substantial improvements in the fluency that they were able to achieve for matching uppercase to lowercase letters. (Binder 1998) Although all participants continued to make errors, they improved significantly in both the amount of time it took them to go through all letters of the alphabet, and the number of letters they were able to match correctly. Further study could be done to determine if participants would make the same improvements matching lowercase letters to their uppercase counterpart, if working to a higher fluency increases retention or to determine if there are any letters that all participants have difficulty identifying and/or matching.

References

Binder, C. (1988). Precision Teaching: Measuring & attaining exemplary academic achievement. Youth Policy. 10(7), 12-15

Binder, C., & Watkins, C. L. (1990), Precision Teaching and Direct Instruction: Measurably superior instructional technology in schools. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 3 (4), 74-96.

Lindsley, O.R., (1992). Precision Teaching: Discoveries and effects. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25, 51-57